DEDICATION:

To my dear Dad, a gentle gentleman, whom I grieve to have lost in recent days.

To my dear Mom, whose memory I cherish; she was a sparkling font of wisdom.

To my dear Aunties, Marjorie, Patricia, Jane and Maisie for their keen interest in family and family history.

They have all ‘gone on ahead’ but they are my inspiration.

We start this genealogy article with a memento mori—sorry to depress you right off the mark, but it’s a reminder that we all have to die. This one comes to you courtesy of the Petrie monument above the family vault in Sligo Cemetery, one side of which you can see in the banner of this article.

Every tombstone by its very nature is a memento mori, I suppose, but the inscription here really drives the point home. If we read between ‘the line,’ it says, “I was mortal like you and I have died—so keep your affairs in order since the same could happen to you at any time.” Actually, given the times, this warning probably had less to do with keeping your finances in order than keeping your soul in good shape for St. Peter’s entrance-to-heaven examination. (Because it might be a pop-quiz.)

In my teens I used to like the following inscription on a grave monument for its ‘chills-down-the-spine factor’:

Remember, friend, as you pass by,

As you are now, so once was I

As I am now, so you shall be.

Prepare for death, and follow me.

I’ve lost my desire to have that on my own tombstone, however. The Petrie monument inscription has more appeal for its brevity and understatement, although the implication that ‘the worst’ could happen at any moment had, perhaps, a little more impact in the age before antibiotics and modern pharmaceuticals. (Blithely disregarding for the moment the fact that some modern pharmaceuticals might polish you off faster than your disease ever would.)

Back then a myriad of diseases and conditions, from tuberculosis to an abscessed tooth, could carry you off to ‘a better world’ with little opposition from the world of medicine. That’s not to say that we don’t have our share of such things in this day and age–call to witness the growing list of antibiotic-resistant superbugs–but our chances of making old bones have vastly improved since the 19th century. There are fewer cholera epidemics from contaminated water supplies, for one thing. For another, more babies survive beyond infancy, and considerably fewer women die as a result of childbirth.

In those days (and our main focus is the 19th century, incidentally), life was a precarious proposition, and especially in the endeavour of procreation. Marriage must have taken great courage on the part of young women. If they, themselves, did not die while having a child, the odds of escaping the monumental heartbreak of burying that child in a few short years were very much against them. Three of my great-grandfather’s four sisters died in their 20’s. One was buried along with her 10-week-old daughter, who died the day after her. More on that later…

I read something a while ago on Jenny Lawson’s blog site that resonated with me. She remembers as a child her grandmother telling her about HER grandmother (her grandmother’s grandmother) from Bohemia, and since Jenny has no photographs of her Bohemian great-great grandmother, she drew a picture of her from her imagination. In the intricate design around the circular border, Jenny inscribed the words: “I miss the people I never met but who made me who I am– and the people I have yet to meet who will make me who I will become.”

While we are, or ought to be, a work in progress until our dying day, I think it’s fair to say that external influences factor into our development much less in later years. However, I can say that I also “miss the people I never met but who made me who I am.” That one statement encapsulates my feelings about my ancestors. I want to know them and I can’t, so I hunt for details about their lives.

I read about what was going on socially and politically at the time in the places they lived, what things they might have done to accomplish daily household tasks, what sort of food they might have eaten, what illnesses they might have suffered, what medical remedies they might have used, what grief they experienced, what financial reverses they endured, what difficulties and impediments they encountered with travel and communications…and so on.

There are scads of things to learn, and a little intuition and rudimentary sleuthing applied to the bare facts provided by marriage and birth registers, census information, obituary notices, etc., can provide an interesting–if not entirely accurate–picture.

And so I feel as though in telling the story of my ancestors’ lives I’m painting an Impressionist landscape–all atmospheric glimmers of light and deepening tints of shadow, behind a watery curtain.

Back to the inscription on Jenny’s imaginary portrait of her great-great-grandmother…I would say that there are basically two ways that our ancestors have made us who we are…

First, by influencing essential morality and lifestyle choices. In cultures where story-telling is a tradition, the elder members of a family might pass on family values from one generation to the next by featuring in their anecdotes an ancestor with personal attributes they consider worthy of praise. One would rarely hear family stories that feature no-good Uncle Earl who wasted his life and dragged the family name through the muck—unless one has strayed from the straight and narrow path, and requires a moralizing lecture!

We have a decision to make when we hear these things. We might accept those family values and use them as guidelines for our own lives—or we might reject them, for whatever reason, and live our lives in such a way as to be as far in contravention of them as possible. Either way, our families have an influence on our outlook and worldview, for good or ill.

Another way our ancestors make us who we are is biological, and we’re learning more and more all the time about the influence of our DNA on the likelihood of developing certain diseases.

But might there also be something in our DNA that predisposes us to have a particular outlook on life? Is it possible that character traits can be passed down to later generations through our genes?

Consider Ernest Hemingway’s family…not only did he commit suicide, but also his father, two of his siblings, and his granddaughter. Is it possible that our genetic heritage can be the source of such attributes as fortitude or fearfulness, patience or impatience, optimism or pessimism? I’m sure that many of us have heard a relative say that a member of the younger generation is “so much like” an older relative in terms of temperament. It makes one wonder.

I really believe that introverts and extroverts (or the particular mix of both that most people are), are born that way, and not necessarily created by early life experiences. So, can that core character attribute be genetic?

Jenny had to draw an imaginary portrait of her great-great-grandmother, and so would I, since I have no photographs of my paternal great-great grandparents George and Mary (Coghill) Bain, or William and Elizabeth (Williamson) Petrie, or George William and Bridget (Boone) Bartlett, or my great-grandmother Elizabeth (Bishop) Bartlett’s parents (for whom I do not even have a name at this point in time), or my great-great grandparents on my mother’s side, Michael and Amelia (Perry) Foote, John and Susanna (Wiseman) Adams, Isaac and Caroline (White) Rideout, and the parents of my great-grandmother Mary Jane (Wilcox) Foote–whomever they might be!

That’s 16 people who are my great-great grandparents. Of course we all have that, as well as eight great-grandparents and four grandparents. My eight great-grandparents are surnamed Petrie/Bain, Bartlett/Bishop, Rideout/Adams, and Foote/Wilcox. My grandparents are surnamed Petrie/Bartlett (paternal) and Foote/Rideout (maternal).

Great-grandparents are near enough in time to find traces of in photographs–if we’re lucky–and in our parents’ memories of their grandparents, if they knew them. I have a 1916-ish photograph of Thomas and Mary Jane (Wilcox) Foote, my mother’s paternal grandparents, as well as a few anecdotes which hint at their characters.

I also have photos of my father’s maternal grandparents, Isaac William and Elizabeth (Bishop) Bartlett, as well as letters and family history relating to them. And photos of my father’s paternal grandparents, Alexander and Georgina (Bain) Petrie, and a great deal of family history relating to them. My mother’s maternal grandparents, John and Charlotte (Adams) Rideout, are a bit of a mystery, since Mom’s mother died a few months after her birth, and…well, it’s a long story, which I’ll reserve for another time.

The most extensive family photographic record I have is for my father’s side of the family…the Bartletts and the Petries.

Since I’ll be talking about the Petries in this article, here is a photograph of my great-grandparents, Alexander and Georgina Petrie…

I’ll be talking backwards, forwards, and all around them (in time)—but they will be the anchor and central focus of this article.

So, what can we tell from the photograph of Alexander and Georgina? Not very much, although it appears that my great-grandmother was petite in stature, and her facial features incline me to say that she had a mild temperament. On the other hand, it is more difficult to guess at Alexander’s personality from his photographic image. He does not engage with the camera as this portrait is being taken, which was in keeping with the fashion of the time. Even so, something about his image made me wonder whether he might have been a stern type of person.

It was therefore a delightful surprise to see him described in James P. Howley’s book, as “a jolly, witty Irishman from the Black North.” [Howley, James P. Reminiscences of Forty-Two Years of Exploration in and about Newfoundland., May, 2009 (St. John’s: Memorial University) p. 1300]

Howley was a geologist doing survey work for the government, and he stayed at The Petrie Hotel when he was in The Bay of Islands area of Newfoundland. He met my great grandfather on a number of occasions, and—bless him forever—wrote about it.

Howley’s comment about ‘The Black North’ has to do with the Roman Catholic-Protestant issues afoot in Newfoundland and elsewhere at the time. ‘The Black North’ refers to Protestantism. Here’s a bit about Howley’s background from Wikipedia that should explain the remark: “James Patrick Howley’s father, a prominent businessman and financial secretary of Newfoundland, had arrived in St John’s from Ireland in 1804. His sons formed an interesting group; they included Michael Francis, the first native-born bishop of Newfoundland, and Thomas, a surgeon in the American Civil War.”

Yes, James P. Howley’s brother was the first native-born bishop of Newfoundland. His remark about Alexander was a bit ‘tongue-in-cheek’ I think. He was an intelligent, engaging man, and I liked him after reading his ‘Reminiscences.”

Howley refers to Alexander in much the same way in at least two other places in the book. On first meeting my great grandfather, Howley says, “Petrie himself is quite a jolly fellow.” (p. 1200) And after seeing him again after an absence, Howley says, “Petrie is as jolly as ever.” (p. 1211) So it seems that Alexander was a personable type of man, in spite of his photographic image.

Look at his eyes in the photo below. I’d guess that he was a vital man with a strong personality, in addition to being thoroughly congenial company. It’s tragic that he died at only 47 years of age. His ‘Last Will and Testament’ supports that sentiment, since there are indications in that document that he was a thoughtful husband and caring father.

I wish I had some of the letters Alexander and Georgina must have written from Newfoundland to their brothers and sisters back in Ireland and Scotland. They might have spoken of such daily concerns as food supplies and clothing–their availability, cost, and suchlike–to give their family members in ‘the old country’ a sense of what life was like in the new. At the same time, I believe I might have been able to glean bits of their character from their words.

My great-grandmother Georgina was the daughter of a ‘Free Church’ Scottish school teacher from the city of Wick in the county of Caithness in northeastern Scotland, so her letter-writing skills must have been every bit as good as her husband’s in an era when female education may have been more practical and domestic than academic. I feel quite certain that she must have written to her family in Scotland.

As for letters in general…I’m a person who cannot throw a letter in the garbage after I’ve read it. It will go in my ‘archive’ shoebox…or, actually, shoeboxes, at this point in time. Even Christmas cards with a small paragraph or two must be squirrelled away.

Family documents of this nature are beyond value to some of us. Too often these records are lost when people who do not know or appreciate their importance become custodians through inheritance. I’m sure that most of us have heard horror stories of someone’s relative being given the responsibility of clearing out an elderly or deceased parent’s home, and kicking all the family papers and photo albums to the curb.

Of course it could be that a letter recipient will answer the letter received, and then just trash it. Not everyone keeps letters (hard to understand, but there you are!). So, while I’m sure that there would have been plenty of letters sent by both Alexander and Georgina, none of that correspondence has likely survived.

Mind you, in spite of that, I cherish hopes that someone ‘over there’—Scotland or Ireland–may have a treasure trove of family correspondence from years ago in an old box in a dusty attic, just awaiting discovery.

But although I have nothing written by my great grandparents, I do have a letter written to ‘Georgy’ by her brother-in-law, my great-uncle William Petrie, brother of Alexander.

It’s dated May 10th or 18th of 1894, almost two years after Alexander’s death in Bay of Islands, Newfoundland, on July 29, 1892, and I believe it concerns Alexander’s property in Ireland, of which I’m sure the widowed Georgina had need.

When Alexander died in 1892 of ‘stomach cancer’ (in quotes because I’m repeating family lore, with no evidence to support it), Georgina was 45 years old, with four children ages 16 (William), 13 (John), 8 (Ethel), and 5 (Annie), and she was continuing to operate the family business, The Petrie Hotel, as a means of supporting the family.

At the time of her brother-in-law’s letter in 1894, two years after Alexander died, Georgina would have been age 47, and her children ages 18, 15, 10, and 7. No doubt her sons were beginning to be of help in running the hotel, but my guess is that she was struggling.

Here’s a photo of the family ca 1899. I guess the date based on the age of the youngest of the family, Annie (left front), whom I would say to be around age 12. If that’s right, then Ethel (right front) would be 15, John (standing, left) would be 20 (b. December of 1878), and William (standing right) would be 24. Georgina would be 52.

Back to the letter…William has written on stationery printed with ‘William Petrie’ at top left and a drawing of a fish immediately below his name. Beginning at centre top are printed the words “Fishery Office” set off by a scrollwork design:

The letter contents are below…

Dear Georgy–

Your letter to hand this morning. I am sorry to learn the contents of it. & I have had a very trying time myself since my father died keeping all things going as when he died he left everything in a bad way—over £2,200 due to the National Bank Ballina & interest and he lodged Alick’s life insurance, my own, & his as security & I have not got mine as yet although my father is dead 10 years this fall. All through I thought George and Tom were corresponding with you. George was at a Fair last February. I heard him say he was going to send you something as he got the benefit of Alick’s and my father’s insurance–

Tom was telling me that Willie mentioned in a letter to him that he intended coming home this summer. We shall be delighted to see him—

A very severe winter just [over?] here and was very much against the spring fishery—

I am getting up in years myself and have 7 grandchildren.

I am writing George this week regarding your letter.

With kind regards,

Yrs Sincerely,

Wm Petrie

There is much to be learned from these few words.

First, William appears to have been a good man, and we know from the newspaper articles reporting his death—which occurred just six months after he wrote this letter—that he was very much appreciated by the townsfolk of Sligo, Ireland.

As the newspaper article describing his funeral procession stated: “The number of carriages, traps, and other vehicles present were computed to number about 200, and they made up a double row of about a mile long.” Then there were all the marchers on foot…the Masons, the session and committee of the Presbyterian Church, the members of the Corporation and the Harbour Board…and the “great multitude of the general public.”

There were other articles about William in the newspapers after his death, and I’ll just provide a portion of this one from the Sligo Independent newspaper of November 24, 1894. The excerpt is a bit lengthy, but it is useful beyond its purpose as a character portrait; providing, as it does, some biographical information that will help you to follow subsequent information in this article–although I have to say that there is some misinformation. When William’s father died, he did not become sole owner of the fisheries. His brother Alexander (my great-grandfather) was co-owner at the time. The writer of this article would not have been aware of Alexander’s existence, since Alexander had been living in Newfoundland for around 20 years—from 1872/3 up until his death in 1892, two years before William’s. I’ve broken the article into paragraphs, for easier reading…

“It is with feelings of the deepest sorrow that we have this week to announce the death, after a short illness, of Mr. William Petrie, of Carrowroe House, the well-known proprietor of the Sligo salmon fisheries. The deceased gentleman was highly esteemed by all who had the pleasure of his acquaintance. Of an open and generous nature, his purse was always ready to help the poor and needy, and no one ever called in vain for his assistance.

It is some forty-four or forty-five years since Mr. Petrie first came to Sligo with his father from the town of Errol, in Perthshire, Scotland, and during the latter’s lifetime Mr. Petrie assisted him on his numerous farms and in the extensive fishing operations which he carried on all around the Sligo coast. At his father’s death, which occurred some ten years ago, Mr. Petrie became sole owner of all his valuable fisheries. He continued to carry on the farming, but his energies were principally directed towards improving and extending the fisheries, thus giving employment to many who would otherwise have had a hard struggle for existence.

At the Rosses Point he was a veritable prince, the people there coming to him for advice and help in times of trouble. The great influence which he had with rich and poor alike was always exerted as a means of doing good, and many a poor fisherman and struggling toiler has good cause to bless his name. Of Mr. Petrie it can be truly said he was most happy when doing good to others. The bathers at the Point will long regret the death of a sincere friend. The deceased was always thinking of their safety and comfort, providing bathing stages and life-buoys, and in many little ways showing his interest in them.

The Presbyterian Church, of which Mr. Petrie was a member, laments the loss of, perhaps, its most generous and valued adherent. His name always headed the list in any good work, and it was chiefly through his instrumentality and influence that a sufficient sum was raised with which to erect a church at Rosses Point for the convenience of visitors during the summer months. Needless to say, his own name appeared at the top of the subscriptions with a handsome donation. It is sad to reflect that he did not live to see this favourite scheme of his become a reality. Yet the influence of his benevolent actions while in life will be felt as time rolls on, and his friends and relations will be comforted when they review a life nobly spent in works of kindness and charity.

On all sides the poor people are heard loudly lamenting the loss of one who brightened many a dark hour for them, and brought comfort to them in their affliction.

The children, too, have lost a loving friend, whose kindly heart beat in sympathy with them in their little joys and sorrows. He was a true friend, a loving and tender husband, and an affectionate and indulgent father…”

…and on it goes! One has to wonder how it is possible for any human to have achieved that level of perfection, but I think we can at least stand ready to salute him for the level of public admiration that he evidently inspired.

Mind you, while it’s good to know that he was a generous and charitable man, the suspicion arises that he may have given until it hurt—since the value of his estate at death was somewhat less than one would expect. Below is an excerpt from a registry of wills…

£2420 in today’s money would be £288,647.59

Converted to USD = $358,197.59

Converted to CAD = $478,981.81

This seems respectable enough, except that we know the Petries were extremely wealthy at one point in time, so by this account their fortunes were much reduced from formerly. Also, William’s cousin, Charles Petrie of Liverpool, seems to be his executor, and not his brothers who were living near to him in Ireland. Ominously, Charles is described in the registry as “a Creditor.” We must pause to wonder how much of the estate value would be going to cousin Charles.

Charles, incidentally, would have been age 41 in 1894, and at this point in time he was approximately seven years away from election to Lord Mayor of Liverpool (1901), and being awarded a knighthood subsequent to his term in office. He was raised from knighthood to baronetcy in 1918.

This is from Wikipedia: “Petrie had salmon fisheries in Scotland and Ireland, and oyster fisheries in Ireland, at Fleetwood and in Essex. He was leader of the Liverpool Conservatives, knighted in 1903 after his term as Lord Mayor, and created a baronet in 1918. He was a Deputy Lieutenant of Lancashire.”

While Charles may have been an agent for the Petrie Fishery when he first arrived in Liverpool, I believe his own independent fishing interests eventually took precedence. There may have continued to be an affiliation, but not in the way that there once was.

Another thing of note from my great-uncle William’s short letter to my great-grandmother Georgina is his remark that he had seven grandchildren and was “getting up in years.” Would it surprise you to know that he was only 53 years of age at this time? Perhaps he was experiencing some ill health. We can’t know, of course, but we do know that his letter preceded his funeral by just six months.

The following is another death announcement for William (there was no shortage!); this one from The Daily Express newspaper, Friday, November 23, 1894. A transcript follows, for better readability.

DEATH OF MR. W. PETRIE, SLIGO

Sligo, Thursday

This morning at nine o’clock Mr. William Petrie, T.C., a prominent figure in the social and political life of Sligo during the past thirty years passed away at the comparatively early age of 54 years. He had been a member of the Sligo Corporation, Harbour Board, Board of Guardians, and Fishery Conservation, where his common sense and energy, in conjunction with his impartiality, were greatly appreciated. At the time of his death he was, in fact, a candidate for municipal honours. He handed in his own nomination on Friday, being then apparently in his normal health, but on Saturday morning he was struck down with Bright’s disease, and never rallying, died this morning. Today all the shops in the town are shuttered, and the flags on the vessels in the harbour are at half-mast.

This little article is useful in telling us something about the nature of the illness that killed him. It seems that he wasn’t ill for very long.

“Bright’s disease” was a sort-of catch-all term for kidney disease, but perhaps more specifically, nephritis…inflammation of the parts of the kidney responsible for the production of urine. It can be acute or chronic, and is considered hereditary–one of the most common genetic diseases. Nephritis causes a build-up of fluid in the body, with resultant high blood pressure, and a variety of other symptoms—none of them pleasant. As this article seems to indicate, William had the acute form, and it took him down, hard.

Returning to William’s letter to Georgina yet again…another thing to learn from it is that mail delivery is not all that one would wish for in terms of efficiency. She wrote to him March 30, 1894; he received it May 9th or 17th of 1894. So, the letter took at least five weeks to go from the Bay of Islands on the west coast of Newfoundland to Sligo on the north coast of Ireland. Much like Christmas card deliveries by our modern postal services. (gratuitous dig at the Canadian post office)

Postal delivery within Newfoundland in 1872, around the time that Alexander first arrived in Newfoundland, was fairly abysmal as well. The excerpt from Rev. Rule’s reminiscences below tells us that it took almost two months for a letter to go from St. John’s on the Avalon peninsula (southeastern Newfoundland) to Birchy Cove in the Bay of Islands (western Newfoundland).

In case you’re wondering about Rev. Rule, he was the first resident Church of England clergyman posted to the northwest coast during the period 1865 to 1872, and made Birchy Cove his headquarters. Birchy Cove was later named Curling in honour of Rev. Rule’s successor, Rev. J. J. Curling, whose tenure lasted for approximately 16 years, 1873 to 1889. Curling is now incorporated into the town of Corner Brook, Newfoundland.

This (below) is from a letter written by Rev. Rule to a correspondent in St. John’s on February 14, 1872…

“Yesterday I received a letter from you dated December 18th, and I have this good news to tell you that the stamp put on it brought it all the way to Bay of Islands without any additional charge. We are it seems, fairly within range of the post office; so that instead of paying an Indian letter carrier a dollar for each letter from the nearest post office at Channel, now we have a post office here and another at Bonne Bay. The postage from here to St. John’s is three cents, but there are no postage stamps here yet …

The despatch of letters just spoken of was the first despatch of “government” mail we have ever had in winter in Bay of Islands…”

[Rule, Rev. U.Z., Reminiscences of My Life, Dicks and Co. Ltd., St. John’s, NL, 1927]

Mail had to come by ship from St. John’s to the post office in Channel, near Port aux Basques–there being no roads linking the east and west coasts of Newfoundland. From Channel, another means of transportation had to be found to carry the mail to the communities further up the west coast. In wintertime, at least, an Indian ‘runner’ (probably using a dog sled) had to be hired to make the overland trip to Birchy Cove.

As for the key content of my great-uncle William Petrie’s letter to my great-grandmother Georgina, no doubt the news he was “sorry to learn” in 1894, had to do with financial difficulties for the Petrie family in Bay of Islands, Newfoundland. Two years later, in 1896, my great-grandfather Alexander’s estate was sued for bankruptcy. He had been dead for four years at the time of that lawsuit.

I expect that the family business, The Petrie Hotel, suffered both from Alexander’s death, and from the troubles that rocked Newfoundland to her core over the next couple of years.

First, we’ll step back to the month of Alexander’s death, July of 1892. The great St. John’s fire happened that same month. There was massive devastation from the fire, and since St. John’s was the centre of Newfoundland commerce and government, there was more than the charred remains of homes and businesses to cope with in its aftermath. I suspect that the later economic crisis (December of 1894), can trace its roots to that catastrophic event.

attrib PD-US, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1800393%5D

This description of the years immediately following Alexander’s death gives us an idea of how bad things were:

“Our successive disasters, the fire of 1892, and the jarring of the political factions, seemed enough to fill up the cup of our woe; but worse was in store for us. Up to fatal Black Monday, 10th December 1894, Newfoundland credit stood high. Our principal monetary institution, the Union Bank, had for forty years maintained the highest reputation at home and abroad; suddenly credit, financial reputation, confidence in both mercantile houses and banks, fell like a house of cards. For several days we were the most distracted country in the world—a community without a currency; the notes of the banks had been the universal money of the Colony—circulating as freely as gold on Saturday, on Monday degraded to worthless paper.

[…]

The misery caused by these failures of banks and mercantile houses was as disastrous, as widespread, and as universal within our border as the bursting of the South Sea bubble was in the United Kingdom.”

[Prowse, D.W., History of Newfoundland, Boulder Publications Ltd., Edition 2007, orig. published: London, Macmillan and Co., 1895.]

The book that I’m quoting from was written by D. W. Prowse in 1895, when the effects of the St. John’s fire of 1892 and the financial collapse of 1894 were still fresh. Prowse’s description of the financial crisis brings to mind the stock market crash on Tuesday, October 29, 1929, but Newfoundland’s Black Monday of 1894 preceded Black Tuesday of 1929 by 35 years.

The St. John’s fire began on July 8, 1892. Great-grandfather Alexander died twenty-one days later, on the 29th, having written his will on the 3rd day of that same month, clearly in expectation that his days were numbered. But as for the fire, he and his family were living on the west coast of Newfoundland, and would not have seen any of the devastation first-hand–even had they been able to look beyond their own troubles during that terrible month.

The capital city of St. John’s is on the Avalon peninsula on the southeastern tip of the island of Newfoundland. That is 416 km (258 miles), as the crow flies, but the direct route across central Newfoundland is impossible, even today. In the 19th century, and for perhaps the better part of the 20th, people had to take “the long way ‘round.” Coastal boats connected the various settlements of people, small outports mainly, which basically rimmed the island.

Newfoundland is the 16th largest island in the world; slightly smaller than New Zealand’s North Island, and slightly larger than Cuba or Iceland.

Here’s a size comparison between my Great-Grandfather Alexander’s former home island (Ireland) and his new home island (Newfoundland). The population statistics are from the year 2015.

Newfoundland (Canada); area: 108,860 km2; population: 479,105

Ireland (Republic of Ireland and United Kingdom); area: 84,421 km2; population: 6,378,000

http://brilliantmaps.com/largest-islands/

In 1869, just prior to Alexander’s arrival in Newfoundland, and six years before his marriage to Georgina in Bay of Islands, the population of Newfoundland was 146,536. [Side note: That year Newfoundland rejected confederation with Canada in the elections.]

In July, 1892, in the absence of telephone communications, people in the Bay of Islands on the west coast of Newfoundland would have heard about the St. John’s fire by telegraph—that service being established to Birchy Cove in 1878. Other communities in 1890s Bay of Islands were Sprucy Point, pop. 101 (which became the judicial centre in the 1890s), Bannantyne’s Cove (pop. 117), Pleasant Cove (pop. 80), and Petries—named for great-grandfather Alexander—with a population of 48.

Petries is still known as such today, although it, like Curling/Birchy Cove, is now incorporated into the city of Corner Brook. There were two other areas of the Bay of Islands known as Petries Point and Petries Crossing, also named for Alexander, as well as Petries Valley, and a waterway called Petries Brook.

The population of Petries increased a little from these early days, as can be seen from each successive Newfoundland census. But in the census of 1945, the population of Petries was still no more than 658.

[Decks Awash, Vol. 18, No. 1, Jan-Feb 1989, Memorial University, Centre for Newfoundland Studies, p. 2]

The previous ‘great’ fire in St. John’s, that of 1846, “began with the upsetting of a glue-pot in the shop of Hamelin the cabinet-maker; the still greater fire of July 1892 commenced in a stable, and was, in all probability, caused by the spark from a careless labourer’s pipe. Commencing on a fine summer’s evening, fanned by a high wind, the fire burnt all through the night, and in the bright dawn of that ever-memorable 9th of July, ten thousand people found themselves homeless, a forest of chimneys and heaps of ashes marking where the evening before had stood one of the busiest and most flourishing towns in the maritime provinces.” [Prowse, pp. 521-2]

Here is a description from Prowse of the aftermath of the St. John’s fire:

“A walk through the deserted streets demonstrated that the ruin was even more complete than seemed possible at first. Of the whole easterly section scarcely a building remained. In the extreme north-east a small section of Hoylestown was standing protected by massive Devon Row, the remainder of St. John’s east had vanished. Of the immense shops and stores which displayed such varied merchandise and valuable stocks gathered from all parts of the known world; of the happy homes of artisans and middle classes…of the comfortable houses…of the costly and imposing structures and public buildings…scarcely a vestige remained…” [Prowse, p. 528]

And so July of 1892 was a calamitous month for both the Petrie family of Bay of Islands, Newfoundland, and the residents of Newfoundland’s capital city, St. John’s.

This small obituary was posted in the Harbour Grace Standard newspaper on August 30, 1892…

[Mr. Petrie, a well known merchant of Bay of Islands, died at that place Saturday last after a lingering illness.]

Corner Brook on the map below will take you very close to the Bay of Islands. I suppose that Alexander was lucky to have attracted any notice to his passing, given the events of July of 1892. Interesting that there was no other identifier than “Mr. Petrie” in his obituary. Evidently there could be only one “Mr. Petrie,” so no other distinguishing marks were necessary.

Harbour Grace, as you can see on the map, is on the opposite side, the southeast coast, on Newfoundland’s Avalon peninsula. It was a significant commercial centre at that time in 1892, having a population in excess of 6,486 (this number comes from the election roll returns).

I don’t know Alexander’s connection to this place, but for his obituary to have been published in the Harbour Grace newspaper, he must have been known to various people there. Possibly the Petrie fishery, when it was operating in Newfoundland, would have been a presence in Harbour Grace—their ships, at least.

[Side note, and unrelated!: Harbour Grace was popular to pirates in the 17th century, with ‘The Pirate King’ Peter Easton having his headquarters for some years after 1602, as well as pirate Henry Mainwaring, after 1614. One of them (Easton) retired to what later became Monaco, in which place he was known as the ‘Marquis of Savoy,’ supposedly with 2 million pounds of gold underwriting his retirement. Mainwaring was knighted by King James I in 1618.]

Of course, Alexander may have been known to people in Harbour Grace who might have stayed in The Petrie Hotel when they visited the west coast.

Alexander and Georgina Petrie had been operating The Petrie Hotel for some years before Alexander died (possibly more than 10), and it was, as are hotels everywhere, dependent on business travellers and vacationers. It could be that the hotel’s Newfoundland business dropped off after the St. John’s fire of 1892, with many travellers staying close to home while reconstruction of the capital city was underway.

There would probably have continued to be visitors from the Canadian mainland, but I suspect that the usual American vacationers were scarce, especially in the year following Alexander’s death…1893.

That year, 1893, was a bad one for the U.S.

The Panic of 1893 was a serious economic depression in the United States that began in 1893 and ended in 1897. As a result of the panic, stock prices declined, 500 banks closed, 15,000 businesses failed, and numerous farms ceased operation. The unemployment rate hit 25% in Pennsylvania, 35% in New York, and 43% in Michigan. Soup kitchens were opened to help feed the destitute. The Northern Pacific Railway, the Union Pacific Railroad and the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad failed.

Then there were the hurricanes. In August 1893 a major hurricane, known as the “Sea Islands Hurricane” struck the offshore barrier islands of Georgia and South Carolina. Over 1,000 people were killed (mostly by drowning); and 30,000 or more were left homeless. The “Cheniere Caminada Hurricane,” Sep 27 1893 to Oct 5 1893, killed nearly 2,000 persons, the vast majority from coastal Southeastern Louisiana.

Also, assuming that the Americans who normally visited the West coast of Newfoundland for vacations were not affected by the Panic of 1893 or the hurricanes, they might still have decided to spend their time and money on a visit to the Chicago World’s Fair, which commemorated the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s first voyage to the New World. It opened on May 1, 1893, and over the next six months had more than 26 million visitors.

My guess is that The Petrie Hotel may not have entertained its usual quota of American visitors in 1893.

Hard times for a wee Scottish widow-woman with four children. That she was no stranger to hard times must have been a help to her…

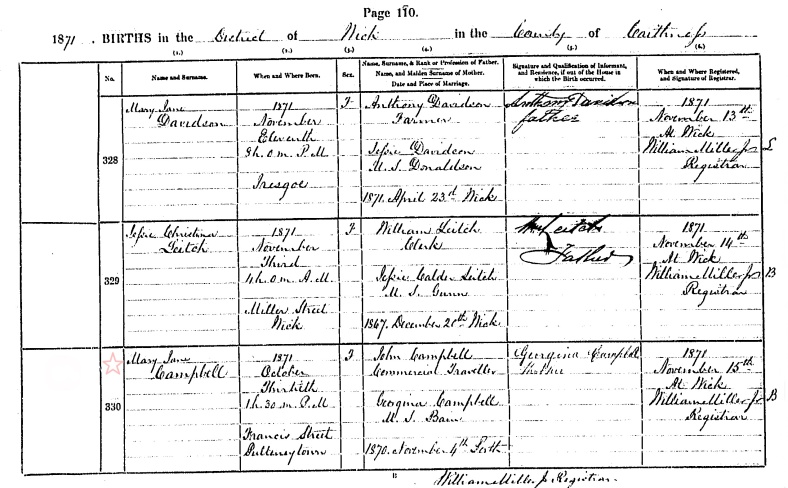

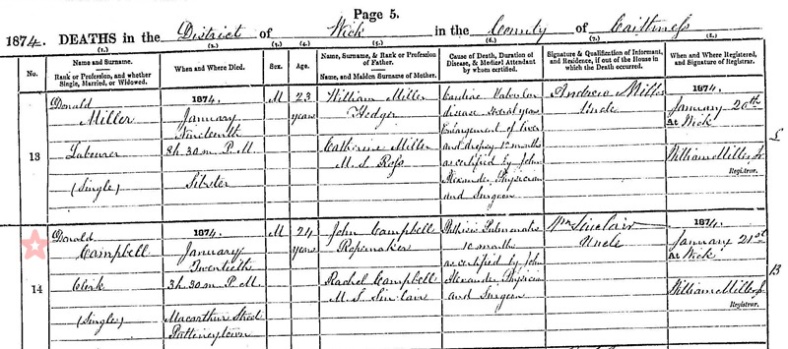

She had been widowed for the first time in her mid-20s (ca. 1873) when her first husband, John Campbell, whom she married on November 4, 1870, died. They were both 23 years old at the time of their marriage…

She had lost her only child (Mary Jane Campbell, b. October 30, 1871) from that first marriage.

While I haven’t yet found the death registry for either John or Mary Jane, I wonder whether John may have been ill at the time of Mary Jane’s birth. Note that the fathers signed the birth registry for the other two babies recorded on the same page as Mary Jane, and that Georgina’s name was written in by the registrar. (Perhaps the registrar didn’t realize that Georgina could write, and never thought to ask.) It’s also possible that John, whose occupation was ‘Commercial Traveller, fish trade’ was just away at the time. The birth was recorded by Georgina on November 15, a little over two weeks after the baby was born.

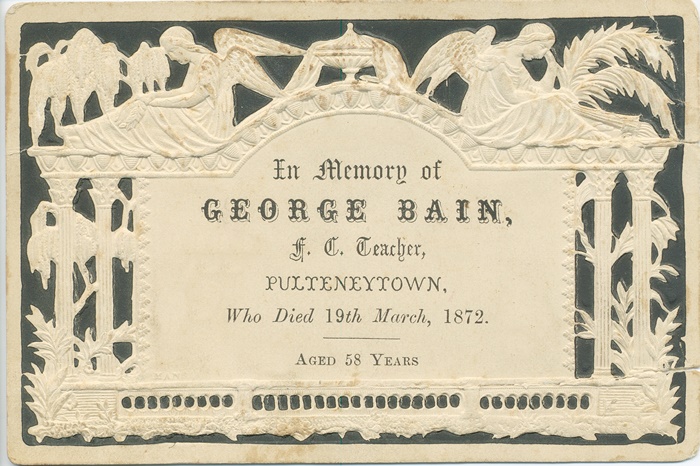

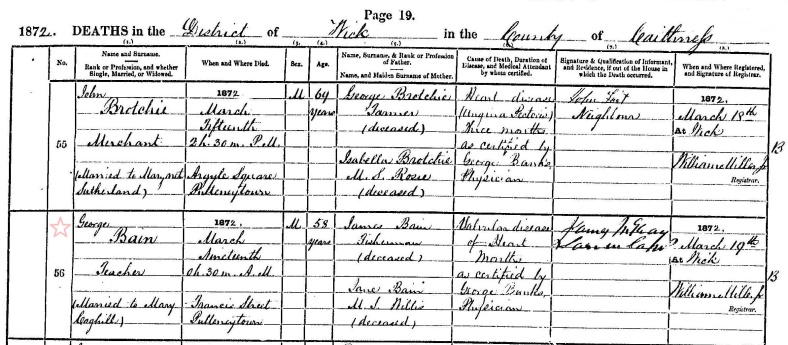

Both of Georgina’s parents died shortly after Mary Jane’s birth. Her father, George Bain, was the first to go, dying at age 58 on March 19 of 1872, when his granddaughter was five months old (assuming she was still alive).

Georgina’s mother, Mary (Coghill) Bain died the next year, on September 16 of 1873, at age 67. George and Mary were buried in the same plot with their 17-year-old daughter, Jane, Georgina’s sister, who died in 1857 of a fever. I believe the gravestone shows Mary’s age as 65, but her birth year was 1806, and her baptism was on March 28, 1806, which would make her age 67 in September of 1873.

The card announcing George Bain’s decease includes the information that he was an “F.C. Teacher”—which means that he was one of the 408 teachers who joined the breakaway Free Church after The Disruption of 1843. “The Free Church was formed by Evangelicals who broke from the Church of Scotland in 1843 in protest against what they regarded as the state’s encroachment on the spiritual independence of the Church.” [Wikipedia] This was an attack on the patronage system, which gave rich landowners the right to select local ministers.

Here’s a news item from the John O’Groats Journal of July 18, 1845, in which my great-grandfather George Bain is mentioned:

“Pulteneytown” which is also shown on the death notice, was a planned town which is now incorporated into the city of Wick in the county of Caithness, Scotland. It came into being in 1808 after The British Fisheries Society commissioned Thomas Telford to design both a new harbour for Wick, and the town, which was to be located south of the river. Pulteneytown was named for Sir William Pulteney, who was the former governor of The British Fisheries Society.

George Bain appears to have died of heart disease, according to the death registry:

Georgina’s sister, Jane Bain, apparently had a fever for 22 days, and died on July 2, 1857. The registry page appears to have her father’s actual signature on it.

Note that on Jane Bain’s death registry page, as well as her father’s, the address is shown as “Francis Street” in Pulteneytown. Georgina’s register of baby Mary Jane Campbell’s birth showed that the baby was born on Francis Street—so possibly John and Georgina were living with her parents. It’s also possible that Georgina went home by herself to have her baby at her parents’ home, with John to join her later. Or maybe John and Georgina lived on the same street as her parents. Or possibly John was no longer in the family picture, and Georgina was widowed and living with her parents…? At the moment, I just don’t know.

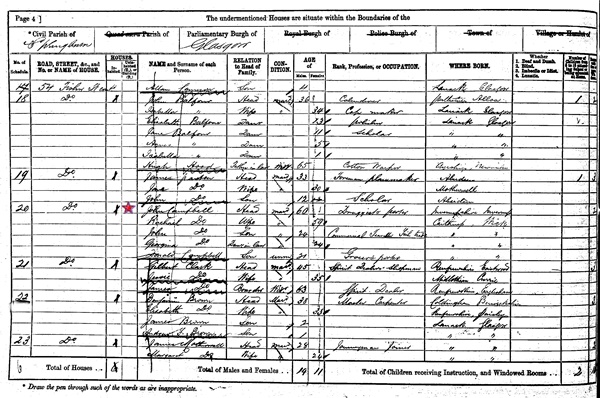

Georgina was living in Perth at the time of her marriage to John Campbell, since the address given for her at that time was 40 Glover Street, Perth. That was also where the marriage took place. Georgina’s older brother, Donald, was a witness. Donald Bain was born in 1842, so he was age 28 in November of 1870 when Georgina and John married. I’m wondering if the house at 40 Glover Street was Donald’s.

John Campbell also had a brother named Donald.

In the 1871 Scottish census, four months after John and Georgina’s marriage, they were living in an apartment building at 54 Fisher Street in the Civil Parish of Springburn in Glasgow with John’s parents and brother: John Campbell, Sr., age 60, occupation: Druggist’s porter, his wife Rachael, age 59, and their son, Donald Campbell, age 21, occupation: Grocer’s porter. The occupation of Georgina’s husband was “Commercial Traveller, Fish Trade” in the census records. Both Georgina and John were 24 years of age at that time. Everyone is recorded as having been born in Wick in Caithness, except for John Sr., who was born in Inverness.

The census was taken early April of 1871 (April 2/3). I would guess that Georgina was two months pregnant with Mary Jane at that time.

This map of Scotland will show you where Georgina’s birthplace–Wick–was in relation to Perth where she was married, and to Glasgow where she lived with her husband and his family after their marriage:

Glasgow and it’s citizens were suffering the effects of a severe housing shortage at the time Georgina and John went to live with his family. There had been an influx of people from the highlands to population centres due to the potato famine and the clearances. Rents were high (due to demand), and wages low (due to competition). Crowded living conditions promoted the spread of disease, especially tuberculosis…

“That tuberculosis was an infectious disease carried by a bacillus was not realised until 1884, and it took much longer to eradicate. In the period 1861-1870, TB killed 361 in every 100,000; in 1901-1910 it was still high at 209. It took until the 1940s and the discovery of penicillin for respiratory diseases like TB to be brought under control. Until that time they remained the main killer.” [Knox, W. W., A History of the Scottish People, Health in Scotland 1840-1940, Chapter 3]

“In Glasgow, one-third of deaths in 1870 were from respiratory conditions, especially tuberculosis (consumption, or TB).”

“Knock-on effects have also been discernible in Glasgow’s housing. While the influx of immigrants in itself created a problem of overcrowding, the low wage economy which they made possible meant that they could also afford little rent to resolve the problem. […] But low wages also combined with higher rents per square foot of floor space, and this so constrained demand, that the nineteenth-century housing built in Glasgow crowded around two thirds to three quarters of households–78 per cent in 1871, 66 per cent in 1911–into one or two room flats, in tenements built high and without gardens to maximise the return on the land. [Williams, Rory, “Medical, economic and population factors in areas of high mortality: the case of Glasgow.” (MRC Medical Sociology Unit, University of Glasgow), p. 174]

I think we can guess how Georgina’s baby came to be born in Wick and not Glasgow on October 30th of that year (1871). For one thing, she probably wanted to be living near to her mother and sisters when she had her first baby. Maybe she was also aware that Glasgow apartment or tenement living was hazardous to one’s health. But mainly I think Georgina realized that living with a newborn baby in the Campbells’ no-doubt cramped apartment would be a nightmare.

That being said, Georgina was no stranger to cohabiting with other family members, since her own family was fairly large. Her parents, George and Mary Bain, had seven children:

James, born in 1833 in Wick David, born in 1835 in Wick Ann, born in 1837 in Wick Jane, born in 1840 in Wick, (died July 2, 1857) Donald, born in 1842 in Kilconquhar, Fife Esther, born in 1844 in Wick Georgina, born in 1847 in Wick

Sisters Ann and Esther seem likely prospects for being a help with the new baby.

I don’t have a way of discovering whether John Campbell’s brother Donald accompanied them to Wick from Glasgow, but he ended up in Wick at some point. His death record tells us that.

Donald Campbell died at age 24 in 1874 of phthisis pulmonalis—an archaic term meaning pulmonary tuberculosis with progressive wasting of the body. Pulmonary tuberculosis is spread through the air when a person with an active infection coughs, spits, sneezes or speaks. There can be a genetic susceptibility to the disease.

His maternal uncle, William Sinclair, provided the information for his death certificate, which indicates to me that Donald’s brother, Georgina’s husband John, was possibly ill himself, or even dead at the time of his brother’s death, or he would have been the one to do this.

Donald and John Campbell’s parents outlived them; John Campbell, Sr. dying in 1885, and his wife Rachael in 1881. Both died in Wick. They had only the two boys in their own family, so when John, Donald and granddaughter Mary Jane died, they had no immediate family remaining, excepting each other.

There was no shortage of sad family stories in those days.

Perhaps John and Rachael Campbell moved from Glasgow to Wick to help nurse one or both of their sons, and ended up staying there. In the absence of evidence to the contrary, I think we might assume that John Campbell died of the same disease as his brother.

And so sometime during the years 1871-1874, Georgina was widowed. I can find no record of John Campbell’s death, but I know that he died during those years. Also, her baby daughter disappeared from the written record, and any evidence of either her death or her continued existence is absent (at least I can’t find it). She did not accompany her mother on the voyage to Newfoundland, which tells me that she was also dead.

As we’ve seen, Georgina lost husband, daughter, father and mother in a few short years.

It has always amazed me that Georgina had the courage to leave her homeland and gamble her future on a new life in Newfoundland, so far from her family in Scotland. Newfoundland was a largely undeveloped place, and sparsely populated, especially on the west coast. But perhaps after undergoing all that grief and loss, emigrating from Scotland to Newfoundland was not the traumatic upheaval it might otherwise have been.

How did she meet Alexander Petrie? While I can’t pinpoint the exact time or place, I think the key to that is John Campbell’s occupation as “Commercial Traveller, Fish Trade.” The Petrie fishery had a base in Wick, so that seems to be the connection.

However, Wick is eastwards from Sligo, and Alexander seems to have been pointed in the other direction entirely. He was moving westwards, possibly first to the Bay of Chaleur, New Brunswick (1869-ish), and then to the Bay of Islands, Newfoundland (1872-ish). So I think that there’s an important piece of their story missing here.

In any event, Georgina Campbell, née Bain, took what was likely a six-week sea voyage on some sort of sailing ship (likely a Petrie Fishery ship), went to Newfoundland, and married Alexander Petrie in the Bay of Islands on March 31, 1875. Perhaps a jolly, witty Irishman of Scottish ancestry was just what was needed to make her think that the future might still hold some promise of happiness.

Possibly her voyage to North America was undertaken on board The Hibernia (or Hibernian?—I don’t trust the accuracy of the newspapers, and I’ve seen records of a ship called Hibernian).

This clipping below talks about the acquisition of a new ship for the Petrie Fishery by my great-great grandfather William Petrie (note: not the William Petrie who wrote the letter to Georgina, but his father).

The Sligo Independent, March 5, 1874:

Since we can’t know how they met and made the decision to marry, we might wonder how well Georgina knew Alexander Petrie. Did she have any misgivings about her decision during that ocean voyage to her new home? It’s not like she could return on the next bus if she found her situation unsuitable or uncomfortable in any way. For the times, it was tantamount to an irrevocable decision, and she would have to make a success of it, come what may.

Since we can’t know how they met and made the decision to marry, we might wonder how well Georgina knew Alexander Petrie. Did she have any misgivings about her decision during that ocean voyage to her new home? It’s not like she could return on the next bus if she found her situation unsuitable or uncomfortable in any way. For the times, it was tantamount to an irrevocable decision, and she would have to make a success of it, come what may.

Consider the visual contrast with the places she’d lived before.

Here’s a photo of her birthplace, Wick, in the county of Caithness, Scotland, where the herring fishery was an important part of the local economy…

“Wick developed rapidly throughout the 19th century. The inner harbour was completed in 1810 and was reconstructed between 1824 and 1831. An outer harbour was built between 1862-7 due to pressure of trade. By the mid-19th century, the town was the largest herring fishing port in Europe, and at the peak of the town’s trade in 1862, an estimated 1122 boats were fishing out of Wick. Francis H. Groome, editor of ‘The Ordnance Gazetteer of Scotland’ (published between 1882 and 1885) said of Wick that, “During the season, in July and August…herring and herring barrels are everywhere to be found along the shore, sometimes occupying considerable spaces along the sides of the streets in the portion of the town nearest the harbour.”

above, with photo: [http://www.ambaile.org.uk]

She married in Perth, where she was apparently living at 40 Glover Street (her brother Donald’s home?). And after her marriage she went to Glasgow to live with her in-laws.

Below is a 19th century photo of Glasgow:

Glasgow had a population in the 1870’s of around 500,000. Wick’s population was more in the range of 8,000 – 9,000, but that was still impressive compared to the population in The Bay of Islands in 1871: there were 947 people, scattered amongst a variety of settlements.

Bay of Islands, Newfoundland, was positively rural by comparison to either Glasgow or Wick (photo from Holloway, below). But I think it had the edge for beauty…

The following description of the Bay of Islands comes from Lovell’s Directory of 1871, in which Alexander did not, as yet, have a business listing.

West Coast – Lovell’s Directory 1871

Bay of Islands

A large bay on the western coast of the island, forming a part of what is called the French Shore. The resources of this portion of the island are quite sufficient to support a much larger population that at present resides here. Indeed, both in the way of agriculture and the fisheries, no section of the country offers greater inducements to settlers than does this section.

The herring fishery forms the staple industry of the people, and is prosecuted with great success. Herrings are taken during the months of January, February, March, May, June, October and November. In the winter months nets are used, which are let through holes and channels cut in the ice, but in summer the herring are mostly hauled in seines. The average quantity of herring annually taken may be stated at 30,000 barrels, most of which find a market in the adjacent provinces.

On the banks of the Humber river, which flows into this bay, large quantities of fine timber are produced suitable for lumbering, which is however, as yet availed of but to a small extent, together with large beds of limestone, and marbles of beautiful varieties, and masses of gypsum almost exhaustless in quantity. The land around is level and capable of easy cultivation, but is availed of merely as an accessory to the herring and cod fishery. The bay is studded with islands and the scenery remarkably fine. Distance from north head of St. George’s Bay 55 miles.

Population 947.”

In any case Georgina’s marriage to Alexander Petrie seems to have been a good decision, even with more difficult times ahead.

She had another child right away, a boy this time (William Thomas, b. September 4, 1875), then lost a child (George Alexander (b. Jan. 27, 1877, d. after May 27, 1877), had a child (John Albert b. December, 1878), lost a child (Samuel Kelly, b. Sept. 22, 1880, d. after Oct 31, 1880), had a child (Ethel Bain), b. Jan. 16, 1884, lost a child (‘Lizzie’), and had a child (Annie Daisy, b. Feb. 6, 1887). I don’t know anything about Lizzie, but George Alexander and Samuel Kelly lived for a short while.

I was a bit puzzled by “Samuel Kelly” as a name for one of Alexander and Georgina’s children, until I realized that Alexander and Georgina’s sister-in-law, the former Elizabeth Kelly, was the daughter of Dr. Samuel Kelly. Dr. Kelly died before his daughter’s marriage to Alexander’s elder brother William in 1861. Alexander would have been 16 years old at that time. What was the connection that would have prompted Alexander and Georgina to name their child after their sister-in-law’s father, twenty years after that man’s death and before he could have had a significant impact on their lives? It’s a mystery to me. Maybe they just liked the name.

This next photo is an old tin-type photograph of Georgina with her two young sons. William would be the older child, and he was likely between three and four years old at this time. Baby John, who was born in December of 1878, was maybe five or six months old. That puts this photo somewhere in the late spring or early summer of 1879. It seems that George Alexander (born in January of 1877) must have died, or there’d be three children in the photo. George would have been around two and a half years old, if he’d lived…

The next major event after the birth of their last child, Annie Daisy, in 1887 was Alexander’s death five years later, at age 47, again (supposedly) due to stomach cancer. And Georgina was widowed for the second time.

She’d had more than her share of grief to this point in time, I’d say. Her losses were: one sister (Jane Bain, who died at age 17), two husbands, four children, and both parents. She was 45 years old.

And, given the economic times, her letter to her brother-in-law looking (I presume) for the inheritance money from Alexander’s property in Ireland must have been prompted by real need.

This is Alexander’s Last Will and Testament:

Petition of William K. Angwin – Estate of Alexander Petrie

Probate year 1892

To the Honorable Sir Frederic T Carter, KC Jn G Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Newfoundland the Honorable Sir Robert J Pinsent DCL and the Honorable Joseph J Little Assistant Judges of the said Supreme Court.

The Petition of William K Angwin of Bay of Islands in the Island of Newfoundland Merchant,

Humbly sheweth

That Alexander Petrie late of Bay of Islands aforesaid Gentleman deceased departed this life on the twenty ninth day of July AD 1892

That the said Alexander Petrie previously to his decease made and published his last will and testament which is hereto annexed marked A that the said will has been duly proved in common form.

That under the said will the said Alexander Petrie appointed his brothers George and Thomas Petrie of Sligo Ireland and your Petitioner Executors of his Estate.

That he left his Widow Georgina Petrie and four children viz William Thomas, John Albert, Ethel Bain and Annie Daisy him surviving.

That the said deceased was at the time of his death possessed of property of the probable value of Five Thousand Dollars.

That no Probate or Administration to the Estate of the said deceased has been taken or applied for.

(part missing) ….may be granted to Your Petitioner in this Island of Newfoundland the rights of George Petrie and Thomas Petrie the other Executors named.

A

The last will and Testament of Alexander Petrie, Gentleman of Bay of Islands, Colony of Newfoundland.

I Alexander Petrie considering the uncertainty of this mortal life and being of Sound mind and memory, do make and publish this my last Will and Testament in manner and form following that is to say

First I give and devise unto my beloved wife Georgina Petrie during the term of her natural life and so long as she shall remain single, all that messuage or tenement at present occupied and held by me, together with all my other liquids and freehold estate whatsoever, situated, lying and being on Bay of Islands, Colony of Newfoundland. At the death of my said wife Georgina Petrie, or in the event of her marrying again, I direct that the land messuage or tenements aforesaid shall go to my sons William Thomas and John Albert in equal shares. And in the event of the death of either of my said sons William Thomas or John Albert before they shall arrive at the age of twenty one years, I direct that the share of the deceased shall go to the surviving brother.

I further direct that from the proceeds of my Life Insurance Policy, my executors shall pay first the amount advanced by my brother William in payment of premiums on the same. Second they shall set aside the sum of One Thousand Dollars which shall be appropriated as they may decide towards the education of my children. And thirdly the remainder of the sum received from the aforesaid policy I devise and bequeath in Equal Shares to my daughters Ethel Bain and Annie Daisy. And I further direct that my Executors shall invest the same and keep the same invested for the benefit of my said daughters and shall pay over to them the interest accrueing there free from the control of their husbands should they marry and at their death I direct that the principal shall be paid over to their heirs or as they may by will direct.

And whereas certain real estate property in Sligo, Ireland, is now held in the name of my brother Thomas, but which belongs to me, I direct that my Executors shall obtain from my said brother Thomas a conveyance of said property to themselves and at such time as they may think advisable I direct that they shall sell the said property and after paying all charges thereon I direct that they shall divide the proceeds thereof between my children share and share alike. And I further direct that the share of each shall be paid over to them when they shall reach the full term of twenty-one years.

And I also give and bequeath to my said children in equal share all the rest and residue of my property of whatever nature or wherever situated.

I hereby appoint nominate and appoint to be the Executors of this my last will and testament my brothers George and Thomas Petrie of Sligo Ireland and William K Angwin, Merchant, of Bay of Islands, Colony of Newfoundland

In witness whereof I have hereunto signed my name and affixed my seal on the third day of July A.D. 1892.

Alexander Petrie

Signed Sealed published and declared by the said Alexander Petrie as and for his last will and testament in the presence of us who in his presence and in the presence of each other and at his request have signed our names hereto as witnesses there of. The words “lands and” having been first inserted on the first page.

John Putnam Halcones

Joseph C Meredith

William Angwin rented his lobster packing business premises from Alexander and Georgina and was mentioned in Howley’s book as residing at The Petrie Hotel, at least at one point in time. As we can see from the will document, he was named one of the three executors of Alexander’s last will and testament; the other two being Alexander’s brothers, Thomas and George, in Ireland.

It’s a little puzzling to me that Alexander’s elder brother and business partner William (author of the letter to ‘Georgy’) was not named executor, but instead Thomas (who was the only one of the brothers not to marry, and who emigrated to Australia around ten years after Alexander’s death in 1892), and George. I’m sure that George was stable enough to be relied on for this task—even though he would have been hampered by distance—but Thomas? In preference to William? Perhaps this was due to the fact that he was holding some of Alexander’s property, and possibly the purpose for that was to keep it separate from any connection to the business.

Alexander and Georgina’s first son was named, “William Thomas,” likely named for Alexander’s father, William, and his brother, Thomas. Since Thomas was given the first honour of a namesake in his brother’s family, I’m guessing there was likely a special bond between brothers Alexander and Thomas. Were they close in age? Not especially…Alexander was born in 1845, and Thomas was born in 1857, so there were 12 years of difference in their ages. Alexander’s other brothers, Peter (b. 1849), John (b. 1852), and George (b. 1855)—even William (b. 1841)—were closer in age to Alexander.

Now, you might want to say that perhaps the reason Alexander named a much-younger brother as executor was because he might reasonably expect some of the brothers nearer to his own age to predecease him, and that there would be a better chance of the youngest brother still being around when needed. But I don’t think so, because Alexander’s will was drawn up not too long before he died, July 3rd to be exact—just 26 days before his death. Maybe he couldn’t be certain of not lasting much longer, but one suspects that he had a pretty good idea.

In any case, Alexander named brothers Thomas and George in Sligo as executors, along with William Angwin, who was local to Bay of Islands, Newfoundland.

I very much like the fact that Alexander wanted to set aside one thousand dollars for the education of his children—note that he does say “my children” and not exclusively “my sons”– and also that he sets aside some funds to be invested for his daughters’ benefits, “free from the control of their husbands should they marry.” He was a progressive, caring father, evidently. I’m not sure that all 19th century fathers thought of giving their daughters an education and a little financial independence—as much as could be provided to that end, that is. The bulk of his property went to his sons, but only after Georgina was done with it.

Back yet again (one last time) to the letter from William Jr., to his widowed sister-in-law, ‘Georgy’ in Newfoundland…the key message we take from it is that finances are a problem–both in Bay of Islands, Newfoundland, and in Sligo, Ireland.

But there are many questions to answer concerning that.

How did things come to this stage, and what happened to the family fishery business? Alexander came to the Bay of Islands, Newfoundland, to open a new branch of the successful Petrie fishery business based in Sligo, Ireland–so what happened? Also…

I knew of the existence of The Petrie Hotel at Pleasant Point, or Petrie’s Point, in the Bay of Islands, Newfoundland, but I had originally thought that the hotel came about after Alexander’s death, as a means for Georgina to be able to support the family on her own.

While it was in fact her sole support after his death, The Petrie Hotel started up many years before Alexander died, and he and Georgina were running it together. The hotel was apparently their primary source of income from approximately 1878 onward, apart from rental income earned by premises let to another business owner, William Angwin (Alexander’s executor, and, I would guess, friend).

The switch from fishery to hostelry in the late 1870’s must have been prompted by some significant events, and so it was.

Did Georgina’s troubles end with her second widowhood? No, they did not. There were more trials ahead…a lawsuit and another family death, for two.

With the daunting prospect ahead of her of being the sole head of the family, did she pack everyone up and return to Scotland or Ireland to live near relatives?

No, she did not.

I said to a friend of mine, “Why would Georgina stay on in The Bay of Islands, when she was alone, struggling financially, and trying to raise four children?”

My friend said, without hesitation, “Because she loved Newfoundland.”

Well of course. That explains it perfectly.

This is the end of Part One.

Great job on your family research. I can tell that was a labor of love for sure. Very interesting and wonderful that you could find old photos too.

LikeLike

Much appreciated!

LikeLiked by 1 person