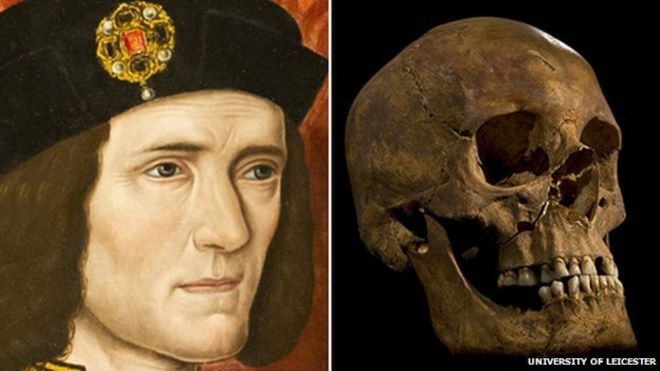

The University of Leicester–who kindly gave me permission to use the images of their 2012 exhumation of Richard III from under the car parking lot in Leicester (England)–tell us that 500 years after Richard was unceremoniously wedged into the ground in the choir of Grey Friars church in Leicester, his skeleton is still almost complete. Missing are his left fibula (lower leg bone), a few small hand bones, some teeth, and his feet–which they say were probably separated from the rest of him during the construction of a Victorian outhouse on top of the grave.

I don’t know what to think about that…the Victorian outhouse, I mean. I was tempted to write to the University of Leicester and ask them whether by ‘outhouse’ they mean an outdoor toilet, as we would refer to it in North America. Could it be possible that they might mean an out-building like a garden shed? Sometimes commonly understood terms in North America mean something a little different in Britain, and vice-versa. In this case, I certainly hope so.

Richard’s skeleton showed dreadful injuries, among which was an ‘insult injury’ as evidenced by a cut to the pelvis–which indicates a stab to the buttocks. Historical accounts say that he was stripped naked after his death, slung across a horse, and paraded in front of many people in that state. A very ignominious treatment for a dead body, no matter whose it is—but maybe especially for a king. The eventual placement of the body in the ground with the head wedged against the upper end of the burial pit is another potential indicator of disrespect to the deceased. And then, centuries later, an outhouse constructed over his last resting place? (Unintentional, mind you, since they didn’t know he was there.)

Perhaps Richard III does have a lot to answer for in the events of his 32-year life and two-year reign, but he would not be unique in that respect among medieval monarchs. Beheading, hanging, drawing and quartering and suchlike punishments for disloyal subjects were commonplaces of the time. “Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown”–from Shakespeare’s Henry IV, Part 2, Act 3, Scene 1—is very apt in describing the siege mentality that must have been an integral part of the medieval king’s daily outlook. Any king that showed weakness, or failed to brutally suppress traitorous actions, might be inviting contenders for his throne. There was more than self-interest in this, since civil wars cost the lives of thousands of people, and there were no social services to offset the impact on a family from the loss of its breadwinner.

For these reasons, young monarchs who succeeded during their minority needed a strong Regent or Lord Protector, and Richard found himself acting for his young nephew in that capacity when his brother (Edward IV) died at age 40 in April of 1483. We cannot say, however, that Richard performed his responsibilities well, since that nephew and his younger brother disappeared–never to be seen again–under the care and protection of Uncle Richard.

Maybe the outhouse wasn’t such a bad idea after all.

But, in fairness, among the many blameworthy actions ascribed to King Richard III are quite a few blatant falsehoods. Also, while we–and people of any stage in history come to that–can look with horror on the murder of two young boys, it was never conclusively proven that they met their deaths at the orders of their uncle.

All that aside (for the moment), the discovery and identification of Richard III’s skeleton by the University of Leicester’s team of scientists and archaeologists–at the prompting of the Richard III Society in Britain, and with their collaboration in obtaining funding–was nothing short of miraculous. They are to be congratulated for their scrupulous handling of the archaeological dig, meticulous identification process, and for providing thorough documentation along with photos and film explaining procedures and findings every step of the way. Fascinating…and extremely well done.

Now we know what happened to him (if not to his nephews). But, as the Richard III Society would tell us, we should all take another look at Richard III’s life and times; and try to glean the truth of it from the available accounts.

Shakespeare’s portrayal of Richard III is compelling for its artistry, and it’s difficult to discount his version of the villain we love to hate–but it does seem a bit severe…

“Never hung poison on a fouler toad. Out of my sight! thou dost infect my eyes.”

[Richard III, Act I, Scene II]

So, let’s start at the beginning of the end…

On August 22, 1485, the 32-year-old King Richard III–the last king to die in battle in Britain–led a charge directly against his rival, Henry Tudor, 2nd Earl of Richmond, and the small party of soldiers surrounding him. Richard had seen from his vantage point that Henry was at that moment vulnerable to attack, and therefore he hoped to bring the battle to a quick end by eliminating the leader of the opposition himself.

This was the crucial moment in the famous Battle of Bosworth–which acquired its name at a point in time 25 years after the battle had been fought. The name known to contemporaries was the Battle of ‘Redemore’, meaning place of reeds. Given that name, it is unsurprising that marshland conditions had to be factored into battle strategy by the opposing forces. Recent archaeology (2009) has located the site of the Battle of Bosworth not far from Stoke Golding, and knowing that the land was marshy in 1485 was key to identifying the exact place.

Richard gambled big with his somewhat rash action attacking Henry, and since he was ‘all in’ he gave it every bit of force and speed he could. He killed Henry’s standard-bearer, Sir William Brandon, in the initial charge and “unhorsed burly John Cheyne,” Edward IV’s former standard-bearer. But Henry’s bodyguards managed to protect him during the onslaught. [Horrox, Rosemary (1991) [1989]. Richard III: A Study of Service. Cambridge Studies in Medieval Life and Thought. New York: Cambridge University Press.]

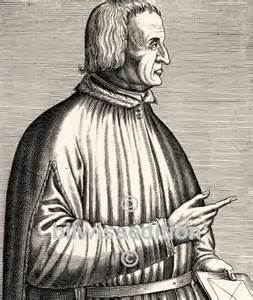

A record of this pivotal moment in British history was written over 20 years later by historian/chronicler Polydore Vergil (1470-1555), an Italian priest who arrived in Britain in 1502. Vergil was commissioned by King Henry VII to write a history of Britain, and began his Anglica Historia in 1506. [www.reformation.org].

Polydore Vergil, 1470-1555

His account of Richard’s attack on Henry follows, and I’ve tried to reproduce the olde English (against auto-correct’s unwelcome assistance) to give your brain a workout! We’ve all done those reading exercises on Facebook and suchlike where only the first and last letters of a word are correct, and the intervening characters are gobbledegook. Vergil’s account shouldn’t be too much of a problem, since there are few words of an antique character…’espyalls’ might be one. We use the verb ‘espy’ or ‘espied’, but we don’t use a noun form that I’m aware of…

Whyle the battayll contynewyd thus hote on both sydes betwixt the vanwardes, king Richard understood, first by espyalls wher erle Henry was a farre of with smaule force of soldiers abowt him; than after drawing nerer he knew yt perfytely by evydent signes and tokens that yt was Henry; wherfor, all inflamyd with ire, he strick his horse with the spurres, and runneth owt of thone syde withowt the vanwardes agaynst him. Henry perceavyd king Richerd coome uppon him, and because all his hope was than in valyancy of armes, he receavyd him with great corage. King Richerd at the first brunt killyd certane, overthrew Henryes standerd, toygther with William Brandon the standerd bearer, and matchyd also with John Cheney a man of muche fortytude, far exceeding the common sort, who encountered with him as he cam, but the king with great force drove him to the ground, making way with weapon on every syde. But yeat Henry abode the brunt longer than ever his owne soldiers wold have wenyd, who wer now almost owt of hope of victory, whan as loe William Stanley with thre thowsand men came to the reskew: than trewly in a very moment the resydew all fled, and king Richerd alone was killyd fyghting manfully in the thickkest presse of his enemyes. [Polydore Vergil, Anglica Historia, Books 23-25, (London: J. B. Nichols, 1846, first published 1556), p. 224.]

No matter what opinion one holds of King Richard III—and Shakespeare’s depiction of Richard III as evil Machiavellian schemer, unscrupulous opportunist and heartless child-murderer is one view—he died valiantly in battle, apparently betrayed by Sir William Stanley, who switched sides (perhaps understandably) at an opportune moment for Henry.

Polydore Vergil goes on to say that Richard had the opportunity to save himself, and didn’t…

The report is that king Richerd might have sowght to save himself by flight; for they who wer abowt him, seing the soldiers even from the first stroke to lyft up ther weapons febly and fayntlye, and soome of them to depart the feild pryvyly, suspectyd treason, and exhortyd him to flye, yea and whan the matter began manyfestly to qwaile, they browght him swyft horses; but he, who was not ignorant that the people hatyd him, owt of hope to have any better hap afterward, ys sayd to have awnsweryd, that that very day he wold make end ether of warre of lyfe, suche great fearcenesse and suche huge force of mynd he had: wherfore, knowinge certanely that that day wold ether yeald him a peaceable and quyet realme from thencefurth or els perpetually bereve him the same, he came to the fielde with the crowne uppon his head, that therby he might ether make a beginning or ende of his raigne. And so the myserable man had suddaynly suche end as wont ys to happen to them that have right and law both of God and man in lyke estimation, as will, impyetie, and wickednes. Surely these are more vehement examples by muche than ys hable to be utteryd with toong to tereyfy those men which suffer no time to passe free from soome haynous offence, creweltie, or mischief. [Vergil, Anglica Historia, Books 23-25, pp.225-226.]

…and so, according to Vergil, King Richard was counselled to take the fresh horses brought to him, and flee. Richard’s reported refusal to save himself was said to be due to his hope of converting his people’s hatred of him to respect by making a brave showing at the battle. As Vergil tells us, he said, “that very day he would make end either of war or of life.”

It’s a romantic account of Richard’s last moments, and presented by King Henry VII’s own historian, whom one would not expect to show his patron’s enemy in any favourable light. But perhaps victory over a worthy opponent (his personal attributes aside) made for a more laudable triumph to Henry.

We might, however, want to question whether Richard was truly hated by his people, or whether Vergil was simply fulfilling his role as political propagandist for Henry VII.

And as for Henry, Polydore Vergil says that “Henry perceived King Richard come upon him, and because all his hope was then in valiancy of arms, he received him with great courage.”

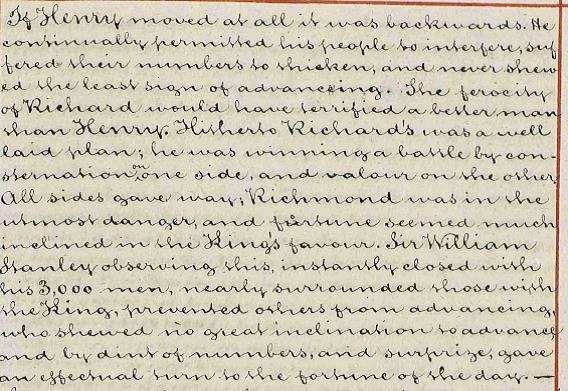

But William Burton’s 1622 The Description of Leicestershire, 2nd edition 1642, printed 1777, differs: “If Henry moved at all it was backwards. […] The ferocity of Richard would have terrified a better man than Henry.”

Burton’s account is below. The final manuscript of the 1642 edition was in folio and transcribed by a professional copyist in a seventeenth-century Secretary hand. I believe the English used in the original text must have been updated with this transcription, but could not find that stated anywhere. I included the handwriting here, which I admire very much for its style and readability…

[William Burton, The Description of Leicestershire, 1622, 2nd Ed, 1642, (W. Whittingham, printed 1777), p. 116.]

[William Burton, The Description of Leicestershire, 1622, 2nd Ed, 1642, (W. Whittingham, printed 1777), p. 116.]

This account tells us that Henry Tudor, 2nd Earl of Richmond, was not the conquering-hero type. We know that he had little experience of battle, and at Bosworth field he relied heavily on the Earl of Oxford, John de Vere’s, greater experience and knowledge. Judging by what we know of his subsequent reign as Henry VII, he could perhaps more aptly be described as an avaricious and parsimonious bean-counter than a valiant warrior.

King Richard III, on the other hand, was a valiant warrior. All sources, even those that disparage his character (which is most–if not all–of them), concur.

But there seem to have been other factors besides valour influencing Richard’s actions at that point in the Battle of Bosworth. While choosing to preserve his own life by taking the horses and retreating to safety might not have earned him respect, a live king would still trump a dead king. Would the cunning and calculating (as he is purported to be) King Richard deliberately press on with a brave but futile encounter with his enemy if there were another choice?

Consider these characteristics of Richard, attributed to him by Thomas More…

He was close and secrete, a deepe dissimuler, lowlye of counteynaunce, arrogant of heart, outwardly coumpinable where he inwardely hated, not letting to kisse whome hee thoughte to kyll; dispitious and cruell, not for euill will always, but ofter for ambicion, and either for the suretie or increase of his estate. Frende and foo was muche what indifferent, where his aduauntage grew, he spared no mans deathe, whose life withstood his purpose. (Thomas More, The Historie of Kyng Rycharde the Thirde, Ed. J. Rawson Lumby, D.D., (Cambridge: At the University Press, 1883), p. 6.)

(Modernized, below…)

He was close and secret, a deep dissembler, lowly of countenance, arrogant of heart, outwardly companionable where he inwardly hated, not omitting to kiss whom he thought to kill; pitiless and cruel, not for evil will always, but more often for ambition, and either for the protection or increase of his estate. Friend and foe were all the same; where his advantage grew, he spared no man death whose life obstructed his purpose.

Thomas More, 1478-1535, Portrait by Hans Holbein the Younger, 1527

However, before wholeheartedly accepting this assessment of Richard’s character, we need to consider the many inaccuracies in Thomas More’s Historie…, and the fact that at the time of Richard’s death at the Battle of Bosworth, More was only seven years’ old. His information was second-hand at best, and possibly relied too much on the biased accounts written by earlier historians/chroniclers. Probably another source was John Morton, Bishop of Ely, who was More’s mentor at an early age. It would be an understatement to say that Morton was not enamored of Richard III.

Also, considering that More wrote the account ca 1513, did not finish it prior to his death in 1535, and the publication of it came about when More’s son-in-law discovered the manuscript and had it published in 1557, one wonders whether More had any intention of completing or publishing it. There’s also some speculation by historians that the history was written by John Morton, Bishop of Ely, and merely copied-out by Thomas More. The following is from the introduction to the volume, and an updated version follows:

“The History of Richard III (unfinished) written by Master Thomas More, then one of the under-Sheriffs of London about the year 1513 Which work hath been before this time printed in Hardyng’s Chronicle and in Hall’s Chronicle, but very much corrupt in many places sometime having less and sometime having more and altered in words and whole sentences, much varying from the copy in his own hand, by which this is printed.” [More, The Historie of Kyng Rycharde the Thirde, Introductory page.]

And so that particular volume was true to More’s handwritten text, but we still might wonder whether the actual source of More’s Historie was John Morton. Another perplexing question is: if Thomas More truly thought that the work had merit and ought to be published, would he not have completed it sometime in the 22 years before he died? (Sir Thomas More—later ‘Saint Thomas More’ when he was beatified in 1886–was beheaded for high treason in 1535 for refusing to recognize that King Henry VIII was Supreme Head of the Church in England.)

And now back to the Battle of Bosworth…King Richard III was on marshy ground in more ways than one. He had reason to doubt the loyalty of his allies, and so his superior numbers (12,000-ish men versus 5,000 on Henry’s side) did not guarantee him a sure victory. For one thing, Richard’s rear guard of 7,000 men under Henry Percy, the Earl of Northumberland, appear not to have engaged with the enemy at all–for reasons that are unclear. Speculation for this runs from treachery to the unfavourable battleground conditions. John Howard, Duke of Norfolk, was apparently loyal to Richard, but his position on Richard’s right flank was threatened by the Earl of Oxford, a seasoned warrior and the leader of Henry’s forces. Norfolk himself was killed in the fighting. Add to this the potential uncertainty about Thomas Lord Stanley’s and Sir William Stanley’s loyalties (Richard had taken Thomas Lord Stanley’s son hostage as security against his father’s support), and Richard’s decision to expose himself to danger becomes more understandable.

So perhaps there was little choice, but this does not diminish Richard’s bravery…

“All accounts attest to Richard’s strength in battle. Even John Rous, who compared Richard to the Antichrist, admitted “if I may say the truth to his credit, though small in body and feeble of limb, he bore himself like a gallant knight and acted with distinction as his own champion until his last breath”. [http://www.historyextra.com/feature/tudors/10-things-you-need-know-about-battle-bosworth]

Additionally, he fought wearing his crown, which made him an easy mark…

Richard was the only English monarch since the conquest who fell in battle, and the second who fought in his crown, an indication of courage, because from such a distinguishing mark the person of majesty is readily singled out for destruction. Henry V appeared at Agincourt in his… [Burton, The Description of Leicestershire, p. 123.]

Richard’s doubts about the support of the Stanley brothers were obviously well founded. We can easily imagine Sir William Stanley observing Richard’s attack on Henry with a calculating eye. At that moment, the outcome of the Battle of Bosworth was clearly in his hands. Two small contingents of men, each containing one of the two key antagonists, were involved in a skirmish—and Stanley’s support could win the day decisively for one or the other. He chose Henry. Stanley surrounded the king’s men with his own, larger forces, and brought the Plantagenet dynasty, and King Richard III, to an end.

Below is Shakespeare’s dramatic recreation of this key moment in the battle, with Richard unhorsed, and looking for a mount to continue the fight. This is from Richard III, Act V, Scene IV…

Catesby:

Rescue, my Lord of Norfolk! rescue, rescue!

The king enacts more wonders than a man,

Daring an opposite to every danger:

His horse is slain, and all on foot he fights,

Seeking for Richmond in the throat of death.

Rescue, fair lord, or else the day is lost!

King Richard:

A horse! a horse! my kingdom for a horse!

Catesby:

Withdraw, my lord; I’ll help you to a horse.

King Richard:

Slave! I have set my life upon a cast,

And I will stand the hazard of the die.

I think there be six Richmonds in the field;

Five have I slain to-day, instead of him.—

A horse! a horse! my kingdom for a horse!

These events were certainly the stuff of which dramatic theatre is made. Only consider the 15th-16th century world in which there were no Hollywood movies, no television programs, no radio broadcasts, no ‘superstar’ actors and no recognizable celebrities. The famous, moneyed, powerful people were the aristocrats, and one had to be careful when representing one of them in an imagination-generated storyline loosely based on fact, because an unflattering characterization could result in dire consequences to playwright and players.

Richard III, the last Plantagenet monarch, was a safe choice for theatrical villain after Henry VII ascended the throne and established the Tudor dynasty. Henry VII’s son (Henry VIII) and grandchildren (Edward VI, Mary I, and Elizabeth I) succeeded him, and Elizabeth was on the throne at the time Shakespeare wrote Richard III. Queen Elizabeth I could have few objections to Richard III’s public vilification, since the Tudor accession–by right of conquest–would gain justification through a perception of superior merit. It might be said that Elizabeth hardly needed that justification, but perhaps her father Henry VIII’s interesting solution to the problem of marital dissatisfaction, and the religious persecutions during her half-sister ‘Bloody’ Mary’s reign were not all that distant in memory. Mary, Queen of Scots, was executed at Elizabeth I’s command in 1587, just five years prior to Shakespeare’s Richard III (ca. 1592), so she was not a supremely confident monarch, secure in her power and position.

Shakespeare’s play, Richard III, draws on Thomas More’s Historie of Kyng Rycharde the Thirde, and it seems that both works paint a much darker picture of Richard III than was warranted by fact.

For one thing, Richard is not suspected of murdering his wife, Anne Neville; she was ill for two months and may have died of tuberculosis. Nor did Richard have marital designs on his niece, Elizabeth, for whom he had been negotiating marriage with a Portuguese prince. He did not kill Anne’s father, the Earl of Warwick, who died at the Battle of Barnet (April 14, 1471). Nor her first husband, Edward of Westminster (son of Henry VI), who died at the Battle of Tewkesbury (May 4, 1471).

King Richard III and Queen Anne Neville, Stained glass, Cardiff Castle

There is also no evidence to suggest that Richard killed Henry VI, who died ca May 21, 1471, while incarcerated in the Tower of London after the Battle of Tewkesbury. It’s possible that Richard, as High Constable of England, might have delivered to the Tower Edward IV’s orders (if such there were) to execute Henry, but there is no documentary evidence of this. There was also a belief by some that Henry may have ‘died of melancholy’ when he heard of his son’s death at the Battle of Tewkesbury. That may seem somewhat fanciful, but Henry’s mental state was known to be fragile; he had had mental breakdowns and suffered hallucinations and lengthy periods of dissociation from his surroundings—modern speculation is that he may have suffered from a form of schizophrenia. Owing to these frequent episodes of mental incapacity, his Queen, Margaret of Anjou, often ruled in his place. She led her own army at the Battle of Tewkesbury, and was taken prisoner by Sir William Stanley until ransomed in 1475 by Louis XI of France.

An interesting side note on this strong, remarkable woman is that both she and Henry shared a love of learning. Queen’s College, Cambridge, was founded in 1448 by Queen Margaret of Anjou, and King’s College by King Henry VI.

Margaret of Anjou and King Henry VI

It occurs to me that if either Edward or Richard wanted Henry VI out of the way, they’d have done better to eliminate Margaret of Anjou.

Richard also does not appear to be responsible for the death of his brother George, Duke of Clarence, who was executed for treason by their elder brother, King Edward IV. According to Horace Walpole in his Historic Doubts on the Life and Reign of King Richard the Third, (Published 1768), “The Duke of Clarence appears to have been at once a weak, volatile, injudicious, and ambitious man.” He seems to have been largely at fault for his own downfall.

Here is an illustration of dubious information provided in Shakespeare’s Richard III, Act I, Scene I, a soliloquy in which the character of Richard says:

For then I’ll marry Warwick’s youngest daughter.

What though I kill’d her husband and her father?

As previously stated, Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick, Anne’s father, died at the Battle of Barnet; and her husband, Prince Edward, son of Henry VI, died at the Battle of Tewkesbury…both fighting against Edward IV, Richard’s brother, and therefore traitors. Richard is unlikely to have killed them.

Anne Neville, Richard’s wife and queen, was Warwick’s youngest daughter. At the time of her young husband Prince Edward’s death at Tewkesbury, she was 14 or 15 years old. She later married Richard at age 16; Richard was 19 at the time.

This excerpt from the play’s dialogue (Richard III, Scene II) has Richard of Gloucester–who was not yet King Richard III–admitting guilt to Anne Neville for the death of Henry VI.

LADY ANNE

Thou wast provoked by thy bloody mind. Which never dreamt on aught but butcheries: Didst thou not kill this king?

GLOUCESTER

I grant ye.

Edward IV is more of a suspect for Henry VI’s death, having more to gain by it. Even so, Thomas More’s History of Richard III explicitly states that Richard killed Henry (which explains why Shakespeare picked this up for his play), an opinion More might have derived from Philippe de Commynes’ Memoir.

Philippe de Commynes (a.k.a. ‘Philip de Comines’) was a diplomat and writer in the courts of Burgundy and France, and lived during the years 1447 – 1511, so he was contemporary with the time of Richard III. He says:

“I had almost forgot to acquaint you that king Edward finding king Henry in London, took him along with him to the fight: this king Henry was a very weak prince, and almost a changeling, and, if what was told me be true, after the battle was over, the duke of Gloucester, who was king Edward’s brother, and afterwards called king Richard, slew this poor king Henry with his own hand, or caused him to be carried into some private place, and stood by himself, while he was killed.” [The Historical Memoirs of Philip de Comines, Book III, (London: Printed by W. McDowell, Pemberton Row, Fleet Street, for J. Davis, Military Chronicle Office, 1817), p. 168.]

Philippe de Commynes, c. 1447-1511

Note that de Commynes says, “if what was told me be true”…a frank statement acknowledging that his source may or may not be reliable.

It’s interesting to see what a foreign king thought about what was happening in England at the time Richard III took the crown. Philippe de Commynes writes of the reaction of Louis XI, King of France…

Our king was presently informed of king Edward’s death; but he still kept it secret, and expressed no manner of joy upon hearing the news of it. Not long after, he received letters from the duke of Gloucester, who was made king, styled himself Richard III. and had barbarously murdered his two nephews. This king Richard desired to live in the same friendship with our king as his brother had done, and I believe would have had his pension continued; but our king looked upon him as an inhuman and cruel person, and would neither answer his letters nor give audience to his ambassador; for king Richard, after his brother’s death, had sworn allegiance to his nephew as his king and sovereign, and yet committed that inhuman action not long after; and in full parliament caused two of his brother’s daughters, who were remaining, to be degraded, and declared illegitimate upon a pretence which he justified by the bishop of Bath… [The Historical Memoirs of Philip de Comines, Book VI, Chapter IX, p. 359.]

It would be helpful to know where King Louis acquired his information about the ‘barbarous murder’ of Richard’s two nephews. We know that Henry of Richmond (later Henry VII) fled to Brittany when Richard’s brother, Edward IV, regained the throne in 1471, and that he lived there for most of the next 14 years under the protection of the Duke of Brittany, Francis II. Did the report of Richard murdering his nephews come to King Louis XI of France via Richard’s enemies?

Not only was there no documented proof of the deaths of the princes, it seems that Henry VII never launched an investigation into their supposed murders upon his accession to the throne after defeating Richard at Bosworth field. According to Horace Walpole in his Historic Doubts on the Life and Reign of King Richard the Third…

No mention of such a murder was made in the very act of parliament that attainted Richard himself, and which would have been the most heinous aggravation of his crimes. And no prosecution of the supposed assassins was even thought of till eleven years afterwards, on the appearance of Perkin Warbeck…

Perkin Warbeck presented himself (in 1490/91) as the younger of the two ‘murdered’ nephews, Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York, returned to England after living abroad. He was captured and interrogated by Henry in 1497.

Henry had never been certain of the deaths of the princes, nor ever interested himself to prove that both were dead, till he had great reason to believe that one of them was alive. [Walpole, Historic Doubts on the Life and Reign of King Richard the Third]

Philippe de Commynes’ report of King Louis XI’s response to Richard’s diplomatic overtures is interesting in terms of timing. Richard began his reign on June 26, 1483, and his coronation was July 6, 1483. King Louis died on August 30, 1483. Below is Philippe de Commynes’ assessment of King Louis XI’s qualities…

In all of them there was a mixture of bad as well as good, for they were but mortals. But without flattery I may say of our king, that he was possessed of more qualifications suitable to the majesty and office of a prince than any of the rest, for I knew the greatest part of them, and was acquainted with most of their transactions; so that I do not speak altogether by guess or hear-say. [The Historical Memoirs of Philip de Comines, Book VI, Chapter X, p. 361.]

Philippe de Commynes seems well aware of the temptation to report ‘guess or hear-say,’ and delivers his lively account of events with wide-ranging information of both anecdotal and historical character, enriched by an analytical and perceptive human viewpoint. He is considered to be “one of the first of the moderns, for his manner and veracity.” [from the Preface to the Memoirs]

It is an unfortunate omission that de Commynes could not tell us how Louis XI came by the information that Richard “had barbarously murdered his two nephews.” In any case, it could only be ‘guess or hearsay’, since there was no official announcement of their demise–natural or unnatural.

Thomas More’s account, on the other hand, begins with a flagrant inaccuracy, in that he says, “Kyng Edwarde of that name the fowrth, after that hee hadde lyued fiftie and three yaeres, seuen monethes, and sixe dayes…” [More, The Historie of Kyng Rycharde the Thirde, p. 1.]

In fact, King Edward IV was not 53 years, seven months and six days old, he was closing in on his 41st birthday at the time of his death on April 9, 1483 (his date of birth was April 28, 1442). More’s statement of Edward’s lifespan is strangely precise for being completely wrong. One almost wonders whether this learned man was leaving his readers a clue to regard the body of the text in the same light as his opening sentence–with scepticism.

With such an inauspicious beginning to More’s account, some doubt might naturally attach to the subsequent information, although it’s difficult to argue with this passage, which refers to the young princes, Richard’s nephews:

For Richarde the Duke of Gloucester, by nature theyr vncle, by office theire protectoure, to their father beholden, to them selfe by othe and allegyaunce bownden, al the bandes broken that binden manne and manne together, withoute anye respecte of Godde or the worlde, vnnaturallye contriued to bereue them, not onelye their dignitie, but also their liues.” [More, The Historie of Kyng Rycharde the Thirde, p. 4.]

Modernized below:

For Richard, the Duke of Gloucester, by nature their uncle, by office their protector, to their father beholden, to themselves by oath and allegiance bound, all the bands broken that bind man and man together, without any respect of God or the world, unnaturally contrived to bereave them, not only of their dignity, but also their lives.

Prior to his own violent end, Richard himself never made any attempt to explain the disappearance of his nephews–at least no attempt that is visible to us. When it seemed apparent that they were dead [the questionable true identity of Perkin Warbeck aside], everyone was left to wonder how, why, when…and even, perhaps, where. It seems likely that their end came at the Tower of London, since that was the last place they were seen alive. ‘When’ is an open question, as may be ‘how’—although More claims to know the specifics from a confession by two of the participants in the nefarious deed. That leaves ‘why’–and too many people had an answer for that.

The Two Princes in the Tower, 1483, by Sir John Everett Millais, 1878

Thomas More writes this condemnation of Richard, and yet adds at the end that some people doubt that the princes were killed during Richard’s reign:

Now fell their mischiefs thick. And as the thing evil gotten is never well kept, through all the time of his reign there never ceased cruel death and slaughter, till his own destruction ended it. But as he finished his time with the best death and the most righteous, that is to say, his own, so began he with the most piteous and wicked: I mean the lamentable murder of his innocent nephews – the young King and his tender brother. Whose death and final misfortune has nonetheless so far come in question that some remain yet in doubt whether they were in his days destroyed or not. [from More’s Historie of Kyng Rycharde the Thirde, p. 93…my update of the language]

More goes on to write this account of the deaths of the young princes…

For Sir James Tyrrell devised that they should be murdered in their beds. To the execution whereof, he appointed Miles Forest, one of the four that kept them, a fellow made for murder before time. To him he joined one John Dighton, his own housekeeper, a big, broad, square strong knave. Then all the others being removed from them, this Miles Forest and John Dighton about midnight (the innocent children lying in their beds) came into the chamber, and suddenly wrapped them up among the bedclothes – so bewrapped them and entangled them, keeping down by force the featherbed and pillows hard unto their mouths, that within a while, smothered and stifled, their breath failing, they gave up to God their innocent souls into the joys of heaven, leaving to the tormentors their bodies dead in the bed.

Which after that the wretches perceived, first by the struggling with the pains of death, and after long lying still, to be thoroughly dead, they laid their bodies naked out upon the bed, and fetched Sir James to see them. Who, upon the sight of them, caused those murderers to bury them at the stair foot, appropriately deep in the ground, under a great heap of stones.

Then rode Sir James in great haste to King Richard and showed him all the manner of the murder, who gave him great thanks and, as some say, there made him knight. But he allowed not, as I have heard, the burying in so vile a corner, saying that he would have them buried in a better place because they were a king’s sons. Lo, the honorable station of a king! Whereupon they say that a priest of Sir Robert Brakenbury took up the bodies again and secretly put them in such place that only he knew and that, by the occasion of his death, could never since come to light.

[More, The Historie of Kyng Rycharde III, p. 84, my update of the language]

More gives as his source for this information the confessions of Sir James Tyrrell and Dighton as they were held in the Tower for treason against Henry VII. Tyrrell was subsequently beheaded for his treason on May 2, 1502, approximately 19 years after the alleged murders of the princes. Dighton was released, as More says, “…in dede yet walketh on alive in good possibilitie to bee hanged ere he dye.” [More’s Historie of Kyng Rycharde the Thirde p. 85] (More evidently does not rate Dighton’s prospects in life very highly.) No documents of Tyrrell’s or Dighton’s confessions, if such there were, survive.

If More, a lawyer, heard–or heard of–these confessions and intended to make them public, wouldn’t a signed document be useful as proof?

Very truth is it and well known, that at such time as Sir James Tyrell was in the Tower, for Treason committed against the most famous prince king Henry the seventh, both Dighton and he were examined, and confessed the murder in manner above written but whither the bodes were removed they could nothing tell. And thus as I have learned of them that knew much and had little cause to lie… [More’s Historie of Kyng Rycharde the Thirde p. 84]

It’s still ‘hearsay’ as we would call it today, unless there is a document to substantiate it, and More is not above using sources of dubious authenticity (again, assuming that he had actually written this account). More has said that he “heard by credible report of such as wer secrete with his chamberers, that after this abhominable deede done, he never hadde quiet in his minde, hee never thought himself sure.” [More’s Historie…p. 85.] Evidently More spoke to someone who spoke to someone who imagined that the king was troubled in his mind owing to some restlessness during the night–no doubt exaggerated in the telling. Polydore Vergil wrote something similar.

While it’s impossible to come to any irrefutable conclusions about Richard III’s involvement in his nephews’ deaths, we do know that he took steps to have their Woodville relatives eliminated quite expeditiously, and with little semblance of a legal trial. On June 25, 1483, Anthony Woodville, Lord Rivers, young Edward V’s maternal uncle; Richard Grey, the king’s half-brother; and Thomas Vaughan, the king’s chamberlain, were all executed at Pontefract Castle, on Richard’s orders, for a supposed ‘treasonous’ plot to deny him his role as Lord Protector.

Lord Hastings, who was Master of the Mint and Lord Chamberlain to Richard’s brother, the late King Edward IV, seemed to be a foot in both camps. He supported Edward IV’s son, Edward V, as the successor, but he appears to have also seen a Woodville (young Edward V’s mother’s family) conspiracy to increase their power and influence during the king’s minority. From all reports, Hastings was a loyal, trustworthy man, who would not, however, have supported Richard’s ambition to be king in his nephew’s place. During a council meeting at the Tower of London on June 13, 1483, Richard accused him of conspiring with the Woodvilles, and had him summarily executed in the courtyard at that very moment, in rather barbaric fashion.

However, there may have been reasons for Richard’s evident suspicion of the Woodvilles. When Edward IV died, Richard was in the north of the country, returning from a successful expedition against the Scots. The young Prince Edward was with his uncle, Earl Rivers, at Ludlow. On the death of her husband…

The queen wrote instantly to her brother to bring up the young king to London, with a train of two thousand horse: a fact allowed by historians, and which, whether a prudent caution or not, was the first overt act of the new reign; and likely to strike, as it did strike, the duke of Gloucester and the ancient nobility with a jealousy, that the queen intended to exclude them from the administration, and to govern in concert with her own family. It is not improper to observe that no precedent authorized her to assume such power. […] Yet all her conduct intimated designs of governing by force in the name of her son. [Walpole, Historic Doubts on the Life and Reign of King Richard the Third, (Published 1768).]

Also, while we look askance at these summary executions, we must consider the times in which Richard III lived, “…we must not judge of those times by the present. Neither the crown nor the great men were restrained by sober established forms and proceedings as they are at present…” [Walpole, Historic Doubts on the Life and Reign of King Richard the Third, (Published 1768).]

Now to move ahead in time and review the remarkable excavation by the University of Leicester on the site of the Grey Friars friary in Leicester in August of 2012.

Grey Friars was originally built in the first half of the 13th century, and named for the Franciscan order, whose garments were a grey colour. The buildings were demolished in 1538, and the building materials used in the construction of other buildings.

In the early 17th century, former mayor of Leicester, Robert Herrick, built a house on the site, with a three-foot pillar erected in the garden containing the inscription, “here lies the body of Richard III sometime King of England”. (As reported by the father of the famous architect, Sir Christopher Wren.)

Subsequent subdivision and selling of the land resulted in the displacement and loss of the pillar, so that Richard III’s final resting place was no longer known.

Parts of the site were built over in the succeeding centuries…houses in the 18th century, a schoolhouse in the 19th century, and offices in the 20th century. The unbuilt land became a car parking lot for the Leicester City Council offices adjacent to it.

The Richard III Society in England, under the leadership of Philippa Langley, were the originators of the project to find the remains of Richard III. The University of Leicester provided all the knowledge and expertise, and broadened the scope to encompass an investigation of the Franciscan friary and its church to gain a better understanding of these structures dating from medieval Leicester.

[This information comes from the University of Leicester website: https://www.le.ac.uk/richardiii/, and all photos of the bones and excavation are used by kind permission of the University of Leicester.]

Three trenches were dug with a north-south orientation, in the expectation that the buildings would be orientated east-west, and therefore the trenches might transect any evidence of wall constructions. The hope was to locate the choir of the church, the most likely spot for Richard III’s remains—IF they were there, and it was no certainty that they were.

Excavating a Trench in Leicester Car Park

Miraculously, the initial digging of Trench 1 uncovered what was later found to be the skeleton of Richard III. Since it was early in the excavation, and there were no other structures as yet identified to provide a location for the remains, they were carefully covered up again. When the cloister walk and choir locations were discovered, the importance of the skeleton in relation to them prompted a careful exhumation, with all precautions taken to preserve DNA integrity…latex gloves, full body suit, etc.

The body was seen to have been placed in the ground with little ceremony, since the head was wedged at an angle to the body against one end. The ground had been disturbed by the foundations of Victorian buildings just centimetres away, and the feet of the skeleton were missing as a result of this later construction.

Bones of Richard III

There was also 19th century brickwork just 90 mm above the skeleton in places and if the Victorian workmen had dug any deeper or wider, the remains might have been severely damaged or destroyed.

The spinal column of the skeleton showed a pronounced curvature, which was determined to be due to scoliosis.

Judging by the length of the thigh bone, Richard would have stood about 5’8” if his back had been straight. The scoliosis would have reduced his apparent height significantly, making him much shorter than the average man in the medieval period. (By contrast, his brother, King Edward IV, was said to be unusually tall, at 6’4”.) Richard’s right shoulder would have been noticeably higher than his left. We can compare this finding with More’s description of Richard III on page 5 of his Historie: “…little of stature, ill-featured of limbs, crooked-backed, his left shoulder much higher than his right, hard favoured of visage…” More’s source evidently got the higher shoulder wrong.

The shape of the individual vertebra supports the finding of scoliosis (photo below). Furthermore, this was determined to be idiopathic adolescent onset scoliosis which is not due to any known cause but may have a genetic component. The two vertebrae pictured below show signs of osteoarthritis…

(Richard has my sympathy in this, since I also have idiopathic adolescent onset scoliosis, and osteoarthritis as a result.)

The skull showed evidence of the sort of injuries which would have occurred in battle, but not to a man wearing the type of helmet used with the body armour of the time. Richard’s head protection may have been dislodged during the fighting, or forcibly removed.

A massive, fatal blow to the base of the skull (#5 in the photo below) was likely caused by a heavy-bladed weapon such as a halberd or an axe, wielded with force. It completely sliced away a portion of the skull. The halberd consists of an axe blade topped with a spike mounted on a long shaft (see insert in photo).

The other fatal wound is indicated by the smaller, jagged hole (#6 in the photo), which may have been made with a sword. Marks on the interior of the skull in relation to this indicate it penetrated to a depth of 10.5 cm.

Another blow shaved off a piece of skull, but would not have been fatal:

Bladed weapon shaved off piece of skull.

There was a slice into the jawbone by a bladed weapon:

Injury to right side of chin: blade cut.

Another wound to the pelvis indicated a possible post-mortem mark of disrespect to the body—a stabbing to the buttocks, as mentioned earlier. This type of injury would not have been possible if the body was encased in armour. It may have happened after death, when the body was stripped naked.

Burton’s The Description of Leicestershire (1642 edition), tells us, “No king ever made so degraded a spectacle…”

[Burton, The Description of Leicestershire, pp. 126-127.]

There were other injuries as well–a small, round puncture wound to the crown of the skull, for example. The totality of injuries tells us that Richard III was ferociously attacked from all sides by multiple people using a variety of weapons.

Richard might now be said to have been in the midst of a fire, and that of his own kindling. He continued his ferocity till his powers and his friends failing, for every one of his followers were either fallen or fled, he stood single in the midst of his enemies, when, becoming less desperate through weakness, many durst approach within the length of a sword, who some minutes before dare not…

[Burton, The Description of Leicestershire, p. 118]

For the purpose of establishing the identity of the skeleton, Dr. Turi King of Leicester University took a tooth and a portion of the femur to grind up for an attempt at extracting DNA for sequencing. It was by no means certain that any DNA could be found to be of use…much depends on soil conditions and suchlike for DNA to have been preserved in a useable state. The tooth was potentially a good source, since the DNA would have been protected from deterioration by the tooth enamel.

Once useable DNA was found, two descendants from Richard III’s sister Anne (Michael Ibsen and Wendy Duldig), contributed their DNA, first to compare with one another (they matched), and then to compare with the skeleton (which they also matched).

Wendy Duldig and Michael Ibsen, (image by kind permission of the University of Leicester)

Since Richard had no surviving offspring, his sister’s descendants were of prime importance, and the mitochondrial DNA, which passes unchanged through the female line, was key to this testing.

A mother’s mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is shared by all her children, but is only passed down to the next generation by females. So Richard III had the same mtDNA as his sister, Anne of York, who passed it to her daughter, who passed it to her daughter, and so on. Finally, that same mtDNA reached Joy Ibsen and her children, Michael, Jeff and Leslie.

[http://www.macleans.ca/society/canadas-connection-to-king-richard-iii-the-inside-story/]

Michael Ibsen is a cabinet maker from London, Ontario, and Wendy Duldig is an Australian now living in London, England. They are two of only four people in the world who share Richard III’s mitochondrial DNA, amongst the millions of descendants of the Plantagenet dynasty. None of these four people have had children, so that the opportunity of testing for identification based on Richard III’s DNA ends with this generation.

Not only was it extremely fortunate that the remains of Richard III were found, it is also fortuitous that they were found at this time, and not a hundred years from now.

This is Michael Ibsen’s Line:

Katherine Roët (Swynford) (+ John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster) -> Lady Joan de Beaufort -> Lady Cecily Neville -> Anne of York (1439-1476) -> Anne St. Leger (1476-1526) -> Catherine Manners (c. 1510-c. 1547) -> Barbara Constable (c. 1530-c. 1561) -> Margaret Babthorpe (c. 1550-1628) -> Barbara Chomley (c. 1575-1618) -> Barbara Belasyse (1609-1641) -> Barbara Slingsby (1633-?) -> Barbara Talbot (1665-1763) -> Barbara Yelverton (c. 1692-1724) -> Barbara Calthorpe (c. 1716-1782) -> Barbara Gough Calthorpe (1746-1826) -> Ann Spooner (1780-1873) -> Charlotte Vansittart Neale (1817-1881) -> Charlotte Vansittart Frere (1846-1916) -> Muriel Stokes (1884-1961) -> Joy M Brown (1926-2008) -> Michael Ibsen

This is Wendy Duldig’s Line:

Katherine Roët (Swynford) (+ John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster) -> Lady Joan de Beaufort -> Lady Cecily Neville -> Anne of York (1439-1476) -> Anne St. Leger (1476-1526) -> Catherine Manners (c. 1510-c. 1547) -> Everhilda Constable (c. 1535-?) -> Katherine Crathorne (c. 1555-1605) -> Everhilda Creyke à Everhilda Maltby (1605-c. 1670) -> Frances Wentworth (1631-1693) -> Dorothy Grantham (1659-1717) -> Frances Holt (1681-1771) -> Frances Winstanley (c. 1703-1766) -> Frances Truman (1726-1801) -> Frances Read (1750-1820) -> Harriet Villebois (1774-1821) -> Harriet Plunkett (1807-1864) -> Frances Gardiner (1828-1907) -> Sophia Lysaght (1861-1945) -> Marjorie Moore (1891-1954) -> Gabrielle Whitehorn (1928-2004) -> Wendy Duldig

As might be expected from rival claimants to the throne, Richard III and Henry, Earl of Richmond (later Henry VII), were second cousins, once removed.

John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, and Katherine Roët (a.k.a. Katherine Swynford, from her first marriage), were:

Richard’s Great-Grandparents, and

Henry’s Great-Great Grandparents

King Richard III (1452-1485) King Henry VII (1457-1509)

Here’s William Burton’s colourful assessment of their characters:

The ruling passion of Henry, after he grasped the sceptre was avarice Had he moved in a servile state, he would like other misers, (the dregs of existence), have denied himself common support, dined upon offals, and his small savings would at his death, have been found in a rag. And Richard’s was ambition This is a laudable passion when guided by reason, but being possessed in the extreme, and under no controul [sic], it proved destructive to many, and in the end to him.

[Burton, The Description of Leicestershire, pp. 65-66.]

Burton adds the following to his character analysis and comparison of Richard and Henry:

The crown was now to be disputed with the utmost acrimony, by two of the ablest politicians that ever wore one; they were both wise, and both crafty; equally ambitious and equally strangers to probity. Richard was better versed in arms, Henry was better served. Richard was brave, Henry a coward. Richard was about 5 feet 4, rather runted, but only made crooked by his enemies; and wanted 6 weeks of 33. Henry was 27, slender, and near 5 feet 9, with a saturnine countenance, yellow hair, and grey eyes. Richard was a man of the deepest penetration! perfectly adapted to form, and execute a plan; for he generally carried what another durst not attempt…

[Burton, The Description of Leicestershire, p. 101]

It’s interesting that DNA analysis points to a 96% probability that Richard III was blue-eyed, and a 77% probability that he was blond-haired. [King, T. E. et al. Identification of the remains of King Richard III. Nat. Commun. 5:5631 doi: 10.1038/ncomms6631 (2014).]

Most blond hair darkens with age, which explains why Richard’s portraits–none of them contemporary–show him with dark hair.

Apparently the arch-top portrait of Richard III (c. 1510-1540) in the collection of The Society of Antiquaries of London comes the closest in representing Richard III’s actual appearance (see below). This portrait is likely a copy of a prototype painted during the king’s lifetime, and unique in that it underwent relatively little overpainting throughout the intervening centuries. Even this small amount was removed by professional conservators in recent years. [https://www.sal.org.uk/news/2014/12/societys-arched-topped-portrait-of-richard-iii-matches-dna-predicted-eye-hair-colour/]

Richard III Portrait, c. 1510-1540, (By kind permission of The Society of Antiquaries of London)

The Society of Antiquaries of London website: https://www.sal.org.uk/

Even though we can probably absolve Richard III of many of the killings for which Shakespeare accuses him, he does seem to have set about eliminating his nephews’ supporters quite ruthlessly.

Also, albeit with some difficulty, he managed to pry his younger nephew, the 9-year-old Duke of York, away from Queen Dowager Elizabeth Woodville, the boy’s mother. She had kept her younger son with her in sanctuary, but eventually, with assurances that he would be safe, she let him go to be with his brother in the Tower. At that point Richard had both princes. If his intention was to eliminate them as rival successors to the throne, he needed them both.

Thus Richerd, without assent of the commonaltie, by might and will of certane noblemen of his faction, enjoyned the realme, contrary to the law of God and man; who, not long after, having establyshyd all thinges at London acording to his owne fantasy, tooke his journey to york, and first he went streight to Glocester, where the while he taryed the haynous guylt of wicked conscyence dyd so freat him every moment as that he lyvyd in contynuall feare, for thexpelling wherof by any kind of meane he determynyd by death to dispatche his nephewys, because so long as they lyvyd he could never be out of hazard;…

[Three Books of Polydore Vergil’s English History, pp. 187-188.]

We might ask Polydore Vergil how he came to know that Richard’s “heinous guilt of wicked conscience did so fret him every moment as that he lived in continual fear…” It seems a thing unlikely to have been known by anyone other than the sufferer.

Vergil goes on to describe in rather dramatic fashion the reaction of the people, and the boys’ mother, when—according to Vergil—the news of the deaths of the princes was made known…

But whan the fame of this notable fowle fact was dispersyd throwgh the realme, so great griefe stroke generally to the hartes of all men, that the same, subdewing all feare, they wept every wher, and whan they could wepe no more, they cryed owt, ‘Ys ther trewly any man lyving so farre at enemytie with God, with all that holy ys and relygyouse, so utter enemy to man, who wold not have abhorryd the myschief of so fowle a murder?’ But specyally the quenes frinds and the chyldrens exclamyd against him, ‘What will this man do to others who thus cruelly, without any ther desert, hath killyd hys owne kynsfolk?’ assuring themselves that a marvalous tyrany had now invadyd the commanwelth. Emongest all others the news herof was unto thynfortunate mother, who yeat remanyd in sayntuary, as yt wer the very stroke of death: for as soone as she had intelligence how her soons wer bereft thys lyfe, at the very fyrst motion therof, the owtrageousnes of the thinge drove her into suche passion as for feare furthwith she fell in a swowne, and lay lyveles a good whyle; after cooming to hir self, she wepeth, she cryeth owt alowd, and with lamentable shrykes made all the house ring, she stryk hir brest, teare and cut hir heire, and, overcommyd in fyne with dolor, prayeth also hir owne death, cawlyng by name now and than emong hir most deare chyldren, and condemning hirself for a mad woman, for that (being deceavyd by false promyses) she had delyveryd hir yownger soon owt of sayntuary, to be murderyd of his enemy, who, next unto God and hir soons, thought hir self most injuryd; but after long lamentation, whan otherwise she cowld no be revengyd, she besowght help of God (the revenger of falshed and treason) as assuryd that he wold once revenge the same. [Three Books of Polydore Vergil’s English History, p. 189.]

Again, according to Polydore Vergil (and we need to bear in mind that he is King Henry VII’s agent, and therefore not sympathetic to Richard III), the king sent an order to the lieutenant of the Tower to murder the princes, and the lieutenant could not bring himself to commit so heinous an act. The king then ordered James Tyrrell to the Tower to carry out the command–which was supposedly done. Richard III then let the news of their deaths circulate amongst the people (according to Vergil), so that they would now understand that since no male issue of King Edward were left alive, they might, “with better mind and good will bear and sustain his government.” However, as Vergil says, this news was apparently received by the populace with great sadness, outrage, and horror.

This would have been such an astonishing announcement–official or unofficial–that had it truly been done, there would certainly have been a record of it somewhere. But there is not.

Vergil goes on to say that the former queen and mother of the murdered princes was overcome not only with grief but with remorse for handing over her younger son (after supposedly being pressured to do so, and deceived by false promises for his safety) to be killed.

Elizabeth Woodville (ca 1437-1492), Edward IV’s Wife and Queen, Mother of ‘the Princes in the Tower’

IF Elizabeth Woodville believed her two sons to have been murdered on the orders of Richard III, we might wonder about her reaction to the appearance of the pretender, ‘Perkin Warbeck’ in 1490/91. Elizabeth died in 1492, and so she would have known before her death about Perkin Warbeck claiming to be her younger son. Would there have been any communication between the two of them? Would she have recognized him had she seen him seven years after his disappearance from the Tower? I’m inclined to think she would still have known whether he was genuinely her son, in spite of the changes seven years would have made. It seems that Henry VII was sufficiently alarmed by Warbeck that he eventually obtained–or forced–a confession from him that he was an imposter, and had him executed on a charge of attempting to escape from the Tower in November of 1499.

As we’ve seen, there are many unanswered questions yet. Leading the quest to re-assess the life and reign of Richard III are the members of The Richard III Society. This is an organization with branches in various countries (Britain and Canada for two) that has attempted to redress some of the false accusations and aspersions on the character of Richard III.

Their patron, the present Richard, Duke of Gloucester, sums up their mission: “… the purpose—and indeed the strength—of the Richard III Society derives from the belief that the truth is more powerful than lies; a faith that even after all these centuries the truth is important. It is proof of our sense of civilised values that something as esoteric and as fragile as reputation is worth campaigning for.”

It becomes an even more difficult mission when an important playwright like Shakespeare embeds a host of misconceptions in a great work of literature. Shakespeare’s Richard III is performed in theatres and on film to this day, and Shakespeare’s plays are still (to my knowledge) entrenched in secondary school English studies. The lines between fiction and fact can become blurred when a play is based on actual events from the past with the names of historical personages assigned to players. Given that many historical accounts already contain conjecture, even propaganda, a theatrical reconstruction takes us another step further away from the truth. The need for heightened drama and exaggeration for entertainment value can further distort an already distorted account of what really happened and why.

And which of the two will be the account we will be more likely to remember? Would it be the school textbook or the Stratford Festival Theatre production of the Shakespearean play?

I think it is fair to say that Shakespeare embellished unreliable historical accounts for dramatic effect, and that Richard III perhaps did not deserve the entirety of the villainy accorded to him. Whether or not Richard could be held accountable for the deaths of his nephews (which would indeed have been a horrible crime), it appears that the historians/chroniclers of the 16th century did let their imaginations run amok—and ‘Shakespeare’ (whomever Shakespeare might have been, since we have questions about him as well), ran with it.

Shakespeare’s primary purpose was to provide entertainment, although his plays contain great insight into human nature in all its variations and permutations. He might also have expected Sir Thomas More’s account of Richard III’s reign to be factual, given More’s reputation. More was not only a well educated man who promoted learning, but also a statesman whose uncompromising adherence to his religious views cost him his life. That Shakespeare might have expanded on More’s account should not be surprising, since the general condemnation of Richard III’s character implicitly granted free rein to the playwright’s imagination. From what Shakespeare would have read about Richard III, he might have deemed him capable of anything.

I took the following from the Richard III Society of Canada’s website:

“Richard was indeed responsible for the deaths of the Woodville conspirators Rivers, Grey, and Vaughan. The Woodville attempt in the late spring of 1483 to have Prince Edward of York crowned and Richard’s position as Lord Protector reduced to a mere title, resulted in the deaths of the three for treason at Pontefract castle, or as Shakespeare has his characters call it, Pomfret.”

The “Woodville conspirators” were the young King Edward V’s family and supporters, and Edward was the rightful heir to the crown. However, Richard was appointed Lord Protector for his nephew by his brother, King Edward IV, and Richard had a duty of responsibility to the 13-year-old king. Had Richard as Lord Protector been shunted aside by the Woodvilles, young Edward would have been under the influence of his mother’s family to a much greater extent. Richard was used to being in a position of power and trust during the reign of Edward IV, and would naturally be unwilling to relinquish it. This put him dangerously at odds with the Woodvilles.

This passage (below) from Walpole’s Historic Doubts on the Life and Reign of King Richard the Third, is, I believe, key to understanding the events of this time. The Woodvilles were elevated in social standing when Edward IV married Elizabeth Woodville, causing great consternation amongst aristocrats (owing to her position as one of the minor nobility). This was compounded by the fact that the powerful Earl of Warwick was at that time negotiating a match for Edward with a French princess, and would not have appreciated appearing foolish and inconsequential to the French.

The ambition of the queen and her family alarmed the princes and the nobility: Gloucester, Buckingham, Hastings, and many more had checked those attempts. The next step was to secure the regency: but none of these acts could be done without grievous provocation to the queen. As soon as her son should come of age, she might regain her power and the means of revenge. Self-security prompted the princes and lords to guard against this reverse, and what was equally dangerous to the queen, the depression of her fortune called forth and revived all the hatred of her enemies. Her marriage had given universal offence to the nobility, and been the source of all the late disturbances and bloodshed. [Walpole, Historic Doubts…]

And did Richard orchestrate the Titulus Regius that declared his brother’s children illegitimate (owing to their father’s supposed engagement to another woman before marrying their mother) and therefore not entitled to inherit the throne? Well, it’s another piece of the puzzle that fits. If it’s true that Dowager Queen Elizabeth Woodville attempted to push Richard aside after the death of her husband–this is how he pushed back. With the Titulus Regius her marriage was discredited, and her power base neutralized.

A defense for Richard has been that once his nephews were declared illegitimate, there would have been no reason to kill them. However, it would always have remained a possibility, if the young princes had lived long enough to challenge the Titulus Regius, for there to have been future wars of succession.

And as for whether or not they were actually dead during Richard’s reign, the key question must be: why is it that when (if) Richard III was widely believed to have murdered his nephews he did not produce them publicly to disprove the allegations? We know that he didn’t. He probably didn’t because he couldn’t. And he probably couldn’t because they were dead. This, of course, assumes that he was “widely believed to have murdered his nephews.” We have that from the “historians” working for Richard’s successor, Henry VII. But is it true?

If his former ally, the Duke of Buckingham, had committed the murders, Richard III could have brought this fact to public attention in 1483 when Buckingham was disgraced and executed for treason. Buckingham would have been a convenient scapegoat–guilty or not guilty–but Richard did not use him for this purpose. Possibly Richard knew it would have diminished his own authority in the minds of the people for Buckingham to have acted independently in such a serious matter. They also might ask why Buckingham was not punished if Richard was aware that he was the killer. And then if Richard didn’t know of Buckingham’s actions at the time, why didn’t he? Implicating Buckingham would still not explain why Richard made no effort to discover the whereabouts of the missing princes, or attempt to explain their absence.

Other than circumstantial evidence and motive, there’s nothing more to implicate Richard. He controlled access to the princes and their safety was in his hands (circumstantial), and their murder would result in the removal of a future threat to his position as monarch (motive). And so it does seem likely.

As it happened, Richard’s own reputation and lack of alliances amongst his nobles may have been the greater threat to the continuity of his reign, as can be seen from the results at Bosworth field. If he believed himself to be reviled by his people (as say the accounts that profess to know his mind on the matter), only a brave and heroic action which would definitively proclaim him victor over his enemy would secure his position. And yet, as William Burton’s, The Description of Leicestershire states, “That Richard was not so little beloved as our historians represent, appears by the veneration in which he was held, long after his death, in the northern countries where he resided in youth…” [p. 131]

But the same publication summarizes Richard’s downfall in this way:

[Burton’s The Description of Leicestershire, p. 106.]

[Burton’s The Description of Leicestershire, p. 106.]

We know for a fact (all sources agreeing) that Richard came to a courageous end in battle, after which his dead body was shown the greatest disrespect. That disrespect continued over the subsequent centuries with the general condemnation of his supposed actions and imagined character. Many would say that he was deservedly maligned, based on his guilt for the fate of his nephews–whether he was directly responsible for their deaths or not.

That he was ultimately responsible for their welfare cannot be denied, and if he brought about their deaths, we might see a glimmer of retributive justice if we believe that Richard III lost the support he needed to win the Battle of Bosworth owing to his treatment of his nephews. That Richard was also not accepted as king by the kings of other countries seems likely in view of Philippe de Commynes’ account of French King Louis XI’s refusal to acknowledge Richard, or to receive his ambassador, after being told that Richard killed his nephews and took the crown for himself.

Two years after Richard’s coronation, when Henry of Richmond was looking for French support in his bid to challenge Richard for the throne in England, King Louis XI’s son, Charles VIII, was on the throne of France. Coincidentally, Charles VIII of France and the murdered Edward V of England were both born in 1470, and both were 13 years old in 1483 when their fathers died and the boys succeeded to the thrones of their respective countries–although Edward was declared illegitimate before his coronation. The French provided ships and men to Henry, and one wonders if the French monarchy’s distaste for Richard was a factor in their decision to assist Henry.

It might be seen that the two young princes in the Tower indirectly brought about Richard III’s own violent death.

With Richard III’s remains recovered and respectfully reinterred 527 years after his death, we’ve had an opportunity to learn much about this infamous 15th-century monarch. We know from his bones that Richard ate luxury items such as fresh fish and game birds, and increased his consumption of wine in his last years. We know from evidence in the burial pit that he had a roundworm infection. We know the extent of his scoliosis and osteoarthritis. We know of his bone-related battle injuries. We know that he was unusually slender, and 5’8” tall, but that his scoliosis would have shortened his stature. We’re pretty sure he was blue-eyed, and that his original hair colour was likely blond before it darkened with age. We know that he was not (Shakespeare, please note), a hunchback, nor did he have a withered arm. And we know, at last, thanks to The Richard III Society and the University of Leicester, where he was buried after the Battle of Bosworth.

But we do not know, for a certainty, whether he ordered the murders of his nephews, nor where their remains might be found. The skull unearthed from the Greyfriar’s site in Leicester might once have contained that knowledge, but it does no longer.

And there are some secrets the bones will not tell.

Excellent article! We are linking to this great article on our site.

Keep up the great writing.

LikeLike

Thanks so much for the kind comment, Jan. Much appreciated.

LikeLike